East African Educational Publishers chairman Henry Chakava (left) with Prof Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o with during a scholars lecture at the University of Nairobi on June 11, 2015.

African literature in English came of age with the works of Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Chinua Achebe, Francis Imbuga, Grace Ogot, Elechi Amadi among others. In popular literature, John Kiriamiti’s My Life in Crime and Son of Woman by Charles Mangua continue to circulate widely.

While the authors’ names soar in popularity, the back-end enablers of literature – shaping their packaging, publication, publicity and availability in local and foreign markets – has remained unknown to many readers.

One of the most significant enablers in Kenya and the region is East African Educational Publishers (EAEP). Started in 1965 as a British-owned multinational known as Heinemann, the company was later acquired by entrepreneurs led by Dr Henry Chakava and operated as such before rebranding.

After 60 years, it is appropriate for book lovers and other stakeholders in the industry to reflect on various influences that have shaped the publisher’s journey, and what other players can learn from the company.

EAEP has had a huge imprint on Africa’s education systems. Its CEO Kiarie Kamau notes how “the set books menu across Africa must have one or more of our books. The River Between, Things Fall Apart, The Concubine, Betrayal in the City and Song of Lawino have been set texts in Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Malawi, Rwanda, Zimbabwe and beyond.”

Apart from investing only in canonical texts, the company has grown other literary staples, including, in Kiarie’s words, “a rich repository of contemporary African literature”.

Some of the authors of classics published by EAEP: From left: Ngugi wa Thiong'o, Ali Mazrui and Chinua Achebe

“From Nigeria, we have works such as Osi Ogbu’s The Moon Also Sets; in Zambia, we have published Hearthstones by Kekelwa Nyaywa, arguably one of the most consequential feminist authors from Africa; and from Kenya, we have Ken Kamoche, among others,” Kiarie said.

The heritage of EAEP is embodied in the company’s first African employee, Johnson Mugweru, who joined Heinemann in 1969.

“We were only three in the company, the Managing Director, Bob Markham, Sussana Markham and myself,” Mugweru said.

Back then, Heinemann would import books published in the UK for local distribution. Soon, the firm evolved into a platform for African voices, mirroring the country’s search for cultural and intellectual independence.

Mugweru retired in 1996, after 27 years with EAEP, during which he rose to head sales, marketing and distribution. During his time at the company, he worked closely with Ngugi and Kiriamiti.

Exposed injustices

“I was also instrumental in the acquisition of titles published by the East African Publishing House (EAPH) when it went under in 1988,” Mugweru says.

In 1972, Chakava joined Heinemann as its first African editor. This allowed the company to prioritise local writers and their realities. Besides fiction in English, Heinemann experimented with Kiswahili translations of publications under the African Writers Series.

Forth came Usilie Mpenzi Wangu (Weep Not, Child) and Mchimba Madini (Mine Boy). Both significantly occupied gaps in the Kiswahili literary market.

In Publishing in Africa: One Man’s Perspective, Chakava recalls his experiment of publishing primary school books in Kiswahili, a language that had been neglected by government.

“The first three books came out in 1980 and were an instant success,” Chakava says of Masomo ya Msingi, the first and only Kiswahili textbooks then, and which my generation read in the 1980s.

Remarkably as well, Heinemann published Ngugi’s first Gikuyu work, Ngaahika Ndeenda – co-authored with Ngugi wa Mirii and also published in English as I Will Marry When I Want – whose politically charged themes provoked the Jomo Kenyatta regime to detain Ngugi in 1977.

The 1980s were dominated by the dictatorial rule of President Daniel Moi, who succeeded Jomo on his death in 1978. Moi’s leadership entrenched a one-party state and tightened political control on the knowledge industry.

Nonetheless, Kenyans remained resilient and activist, relying on Heinemann and other publishers to produce literature that challenged raw power, exposed injustices and condemned the corruption that Moi enabled.

The turbulence of the 1980s gave way to hope in the early 1990s when the clergy, civil society and global partners cornered Moi to repeal the one-party system, paving way for multipartyism.

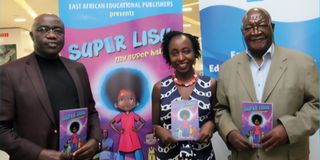

Henry Chakava and his daughter, Yolanda Chakava, during the launch of her children's storybook, Super Lisu. Also in the picture is Kiarie Kamau, CEO of EAEP.

A similar push from the West led to liberalised markets, privatised state corporations, restructuring of the civil service and opening up Kenya for an open but challenging economic vibrancy.

Heinemann underwent transformation too, becoming fully Kenyan-owned under Chakava, who oversaw its rebranding to EAEP. The rebranding signalled the company’s determination to champion African-centred storytelling by privileging locally grounded textbooks.

When Achebe dismissed foreign published storybooks for children as “beautifully packaged poison”, he gave vigour to firms like EAEP to invest more in locally-authored books. Thus, throughout the 1990s, the Kenyan publisher’s catalogue flourished with engaging works for children, with Achebe releasing Chike and The River.

The hope that began in the 1990s peaked a decade later when Moi’s 24-year presidency ended in 2002. Mwai Kibaki succeeded him with the understanding that spearheading Kenya’s economic revival was urgent.

Empowered African society

A plank in this was implanted in 2003 by introducing Free Primary Education, which brought millions of children into classrooms.

Ironically, this period eroded EAEP’s hold on the market. The company suffered a downturn, with its revenues dipping, ushering in a decade of apathy and heavy staff turnover.

Through this business turbulence, however, Kiarie Kamau, who had joined the publisher as editor in 2001, soldered on, enduring a decade of uncertainty all the way to 2015 when he was appointed CEO.

Kamau saw his primary task after the promotion as stabilising the company. This task called for bold and unpopular decisions, including business process re-engineering to enhance efficiency, production and elevate the quality of publications. Today, the publisher is thriving, despite usual impediments that plague businesses.

On whether the death of Chakava has had an effect on EAEP, Kamau said: “He had a futuristic succession plan, which he implemented gradually.”

This, mainly related to structuring the company, entailed allowing continuity with well-timed introduction of his daughters – Andia and Sharon – to take up senior positions in the company.

Andia sits on the Board of Directors while Sharon is on the Management Team as the Operations Director.

Current Board Chairman, Dr Abel Muriithi, joined as a director in 2000, and steered the company as acting chairman for six years during Chakava’s illness that later claimed his life.

To stay ahead of time, the publisher has expanded beyond the traditional print books into interactive digital content, e-books, audiobooks among other modern media.

This is in line with Sharon Chakava’s belief that the “future of publishing in Africa lies in strategic collaborations and partnerships. It also calls for bold experimentation with emerging media. And so, there lies EAEP’s future.”

The Competency-Based Education has also been a shot in the arm and the company’s foothold on the continent is expanding.

For EAEP, it has been 60 years of shaping an educated, informed, and empowered African society.

The writer is Advocate of the High Court and Associate Professor at the University of Nairobi