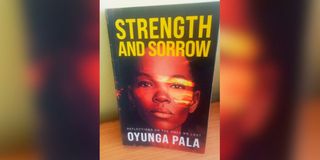

The cover of Oyunga Pala’s new book titled Strength and Sorrow.

When growing up, children were warned not to go out of the house at night because koko would eat she or he who dared to leave the house. No one explained what koko was to us. Grownups assumed that children would be kept in their place by the thought of this strange creature.

But there were much more feared creatures: the roaming spirits of the dead. We weren’t allowed to speak about death. If you dared to, it was in whispers. The dead could listen to what the living said and if it annoyed them, they would harm us mere mortals. It is not surprising that even in adulthood, many people don’t imagine or speak about death in everyday conversation.

So, it would be a little bit scary for those who grew up forbidden from discussing death to have to read Oyunga Pala’s book, Strength and Sorrow: Reflections on the Ones We Lost (2025), especially at night. The author must have known stories of spirits prowling at night, some seeking comfort and peace for having been abandoned out there in; others looking for those to hurt out of malice or because the humans are in the wrong place at the wrong time; the benevolent ones, good relatives and ancestors, watching over the homes of those yet to join them, which abound in his ancestral land. Thus, the reader can only conclude that Oyunga chose a tough subject to write on.

Who wants to talk about death unless they are faced with one - either a member of the family, a friend, a colleague or an associate has passed on? Just think about it. Death is one subject that the living speak about in metaphors, whispers, fearfully or reverently. Generally, death is feared. But why?

There are no quick answers to this question. It is a question that philosophers, theologians, priests, doctors, healers, the local wisewoman or wiseman or even drunk etc are still struggling with. Consider how doctors get shocked when a seemingly ‘healthy’ person, the one who takes every known health caution or doesn’t indulge in activities that would be deemed risky, just collapses one day and dies.

The postmortem may or may not reveal what could have caused the death. The spiritual-minded ones would declare that the fellow’s time on earth was up, as may have been deemed by the spirits or some god. Some philosophers might suggest that all that precaution was in vain because life is nothing but preparation for death.

How then should one read Strength and Sorrow? There is no preferred method of reading a book on a subject such as death because it constantly reminds one of mortality. But Oyunga offers some guidance, not the professional kind as a “certified executive coach specializing in ‘grief alchemy’” - whatever that is. The one way Oyunga seems to suggest how to deal with grief is the old, tried and tested one. Mourn by revisiting the ‘good old memories’ of the time and moments spent with the departed - grandparents, parents, siblings, friends etc.

Near-death experience

The story of his own grandmother’s life and death is one that many Kenyans have lived, know well but would hardly speak about. Yet, grief is a dividend of the direct social relationship with the ‘ones we lost.’ Can one really mourn those that you do not have some kind of close attachment to? Think of why a burial can be held in one home but the immediate neighbors just don’t seem bothered. That fence between the two homes may not just be physical, but also emotional.

Therefore, in many senses, mourning is a very personal experience. Many of the suggestions and claims about how one would like to be on their deathbed (assuming the grim reaper will arrive when the individual is on a bed); to be remembered after dying (the so-called heritage business); how to be treated when dead, including the rituals of burial and mourning, are really just that: wishes. What really do the dead have to do with the living; or why would the living be bothered about the dead?

All those wishes can end up in the wind when circumstances don’t allow it. Think of the court battles in this country over the wealth of a departed relative. The living can and often do ignore the wishes of the dead, keeping the body in some mortuary even for years, because they are squabbling over burial grounds, who has the right to bury the remains of a relative or what portion of the estate to be inherited. All this time, distant relatives and non-family members will keep off the affairs of the concerned family.

Because grief is so personal, it manifests itself differently. The same siblings will mourn their parents in different ways. Some will only worry about the absence of a guiding hand in the family; others will worry about the likely disintegration of the ‘home/house/family/clan’; the entire family might even be gripped by the fear of the unknown such as the likelihood that more members of the family could die from what killed the late or the spirits of the dead might soon come to call a relative to the land of the dead.

Still, how each one of the family members processes the death of a relative doesn’t even begin to demystify death. However, Oyunga suggests that “… A sudden encounter with death, the process of dying, or a near-death experience, demystifies death. This is because the process of dying is sanitized. When we talk about preparing for death, we often mean the dignified process of setting our affairs in order, writing a will, and planning a funeral befitting our stature.”

But to be with a gravely ill patient sometimes doesn’t necessarily invite contemplation about death. In many cases, people push the thought and fact of death to the back of their minds; instead they seek a miracle, a healing or recovery beyond what facts might suggest. Writing a will is a modern invention that seeks to settle disputes, in case they arise but there is enough evidence to suggest that a will may not even begin to address the complexity of the life of the departed or settle the disputes among the living.

The writer teaches literature, performing arts and media at the University of Nairobi. [email protected]