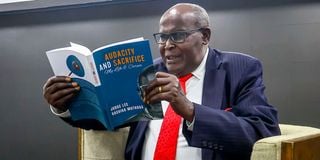

Judge Lee Muthoga during an interview at a media engagement forum on his memoir titled 'Audacity and Sacrifice' in Nairobi on November 12, 2024.

A new book by lawyer Lee Muthoga has rekindled the controversy over the burning of a file that “mysteriously” appeared in politician JM Kariuki’s house after his murder, also revealing what made President Daniel arap Moi agree to re-introduce multiparty democracy in Kenya. That’s not all.

Thanks to the book, the reader gets to see a firebrand who brandished a machete to threaten his teachers after being expelled from secondary school but went on to do relatively well in life.

Among other historical moments is the 2003 Busia plane crash, whose investigation team Mr Muthoga led, and the trial of Charles Njonjo that somewhat feels like the impeachment former Deputy President Rigathi Gaghagua recently went through.

Mr Muthoga’s book, Audacity and Sacrifice: My Life & Career,was launched in Nairobi on Tuesday.

Speaking at the launch, Mr Muthoga, 79, said he chose “audacity and sacrifice” because any leader needs such qualities.

“If you don’t have either of those, quit leadership; become a follower,” he said.

The 1975 murder of politician Josiah Mwangi (JM) Kariuki was shrouded in many mysteries, and one of them was the burning of the file.

Mr Muthoga had been JM’s lawyer for years before his death.

That controversial burning of the file was a sticky point for Mr Muthoga in 2011 when he sought to be the first chief justice under the 2010 Constitution.

Retired Justice Willy Mutunga was the eventual winner of that process, in which Mr Muthoga told the panel that there was nothing they were trying to conceal by burning the file. The contents of the file are contested.

While one of JM’s widows has previously claimed that it contained his will, Mr Muthoga asserts otherwise. He explains that the file mysteriously appeared in JM’s house.

“I continued supporting JM’s family and helping them manage the dynamics within the three households [JM had three wives]. Sometime after JM’s funeral, a blue file was found in the living room at JM’s home in Kanyamwi Farm in Gilgil. It contained duplicates of JM’s income tax records — which could ordinarily have been kept by the income tax department and not the taxpayer,” he writes.

“No one claimed responsibility for the presence of the file in the house. Those present confirmed that it had not been there the day before and no one had keys to JM’s safe, where he kept sensitive documents. All three of JM’s widows…JM’s sister Rahab Mwihaki and myself unanimously decided that we should burn the file, suspecting it was placed there with dubious intentions,” he adds.

“Later, the Nairobi Law Monthly claimed that this burnt file was JM’s will, which was untrue, as everyone had inspected the contents of the file. I continued acting for the family in various legal matters and trying to reach an agreement on the division of his property. Having failed to get the family to agree on the property division, I surrendered the matter to the Public Trustee in 1986,” Mr Muthoga further writes.

Judge Lee Gacuiga Muthoga's memoir titled 'Audacity and Sacrifice' pictured, at a hotel in Nairobi on November 12, 2024.

A property dispute involving JM’s widows has been dragging on in the courts for nearly 40 years now.

Away from JM, whose death Mr Muthoga says left him devastated because he had lost “a friend and benefactor”, another detail he brings to the fore in the book is the day Kenya’s second president agreed to repeal Section 2(a) of the independence Constitution, which allowed a return to multiparty democracy.

Mr Moi caught many unawares by making the announcement at a national delegates meeting for the Kenya African National Union (Kanu) party.

Mr Muthoga claims the President’s decision was partly a result of his meeting with the country’s second commander-in-chief.

Mr Muthoga was part of a 19-member team headed by the late George Saitoti which had been commissioned by Mr Moi to go round the country to collect views on how to make Kanu have a better image and be more responsive to emerging dynamics, among others.

Only four of the 19, Mr Muthoga writes, were not Kanu stalwarts. He was among them.

The others were Archbishop Arthur Kitonga, The Reverend John Gatu and Mrs Eddah Gachukia. The team visited major towns in Kenya in July and August 1990.

What was set out to be a Kanu fact-finding ended up being a collection of the grievances that people had against the government, and Mr Muthoga recalls encountering a strong opposition to the single-party rule.

“Overall, the hearings revealed a consensus by the citizens that the time was ripe for the introduction of multiparty politics,” he says.

The team met to discuss the report they would send to the president. The point on multi-party politics was contentious. The non-Kanu members felt there was a need to incorporate the citizens’ views.

They thought they had carried the day until some committee members “secretly revised the report that night” to state that the public was overwhelmingly in support of a single-party state.

“As the four non-Kanu members of the committee, we felt that we should write a separate minority report expressing the actual views of the Kenyan people. However, since we were outnumbered, we opted to give the president our minority report orally,” writes Mr Muthoga.

That is how they met Mr Moi at 7am on the day the delegates conference would be held. There, he writes, the four spoke in turns.

“The president had not yet read the final written report, and he listened to us attentively as we explained our joint position. We stated that even though the committee’s report recommended continuing single-party rule, most Kenyans desired a multi-party electoral system. The president did not interrupt us as we spoke; he only offered us more tea,” writes the lawyer.

The late politician Josiah Mwangi (JM) Kariuki.

Shortly afterwards, as Mr Muthoga and the three others headed for the Kanu conference, Mr Moi also met a group of diplomats.

At the conference, Mr Moi criticised a multi-party system, but he dropped a clincher towards the end.

“Mimi naona tuondoe ile Section 2(a) ya Katiba ya Kenya [I feel that we should repeal section 2(a) of the Kenyan Constitution,” Mr Moi said.

Writes Mr Muthoga: “The president’s statement caught the Kanu delegates off-guard. He directed the Attorney-General, Mr Amos Wako, to draft an amendment to repeal Section 2(a) of the Constitution within 24 hours. The single-party regime had run its course.”

Kenya was a single-party State, governed only by Kanu, between 1982 and 1991.

Years earlier, Mr Muthoga had been the lead prosecution counsel in the Njonjo matter.

Mr Njonjo was the subject of an investigation following the botched 1982 coup, and the man who led the presentation of charges against him was Mr Muthoga.

Among those defending Mr Njonjo was Paul Muite, who was recently also involved in the defence of Mr Gachagua on his impeachment case.

He writes that he was approached by Mr Simeon Nyachae, then the permanent secretary in the Office of the President.

“Upon noting my hesitation, Mr Nyachae asked me if I wanted him to report to the president that I had declined his appointment, which I interpreted as a veiled threat,” he writes.

He agreed to take up the job but he gave his conditions, among them that he would be lead counsel. Eventually, seven out of 13 accusations against Mr Njonjo were confirmed, among them that Mr Njonjo was among the plotters of the coup. However, Mr Moi chose to pardon him.

Regarding his background, Mr Muthoga reveals that he was quite a strong-willed boy who fell out with his teachers quite often.

He grew up in colonial Kenya and witnessed the ills of the government clamping down on perceived dissidents, and that changed something in him.

In one instance, he was expelled from St Paul’s High School in Embu when he was a Form Four boy in 1964.

“The quality of the food we had been getting was unpalatable, so we decided to boycott it. I addressed the students in the dining hall, ‘This food is so bad that even the headmaster won’t feed it to his dog,’” he writes.

That put him on a collision course with the school head, a Fr Lenta, who entered the hall as he was speaking.

“He asked me to follow him to his office, telling me he was expelling me from the school. I walked to the school store, returned to the office with a panga (machete), and brandished it in Fr Lenta’s face, saying, ‘If I do not sit the examination in this school, someone will die here today, and it won’t be me!’ The commotion made one teacher emerge from the staffroom next to the headmaster’s office. He grabbed my hand and took the panga away,” writes Mr Muthoga.

He was expelled, and that was not his only run-in with school administrators. As a university student in Tanzania, he was among a group that defied an imposed ban and sent an angry telegram to President Jomo Kenyatta in 1969 after the shooting of Tom Mboya in 1969.

Mr Muthoga, a Senior Counsel since 2006, is a towering figure in Kenya’s legal system who has mentored many.

He was one of the pioneering indigenous lawyers in Kenya, getting admitted to the roll of advocates in 1971 and starting a law firm in 1975.

He was elected as the chairman of the Law Society of Kenya in 1981. He has held various government appointments over the years, among them chairing the Sales Tax Appeals Tribunal (1985), chairing the VAT Appeals Tribunal (1990), chair of the Insurance Appeals Tribunal (2010), among others.

In 2003, he was elected as a Judge of the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. The tribunal was based in Tanzania, and that’s where he mostly lived till his work at the tribunal ended in 2012. He even bought a house in the neighbouring country.

In the same year he took up the Rwanda tribunal duties, he headed the team that probed the plane crash that happened in 2003, affecting many officials in the nascent administration of President Mwai Kibaki.

They were returning from a homecoming party for the then Funyula MP Moody Awori.

The crash killed Labour Minister Ahmed Khalif and both pilots. Lawyer Wanjiru Kihoro was also severely injured and died in 2006 after being in a coma since the day of the accident. Survivors of the crash included Ms Martha Karua, Ms Linah Jebii, and Mr Raphael Tuju.

“The team investigated the aircraft accident to establish its cause and make the most appropriate recommendations. We held hearings in Nairobi and Busia, gathering evidence from survivors and witnesses,” writes Mr Muthoga.

“Our investigation revealed that a combination of human error and the poor condition of the runway at Busia led to the accident,” he adds, noting that they made recommendations that changed the aviation space in Kenya.

Did you know what motivated Mr Muthoga to become a lawyer?

Well, he was so angry at being denied a lift that he wanted to be a judge to sentence that driver to death. At that time, the death penalty was on everyone’s lips because of what freedom fighter Dedan Kimathi had gone through.

He was 12 years old in 1957 when he was walking home from school with a friend. As a ploy to get a lift after spotting an oncoming car, his friend, Karimi, lay down and pretended to be sick as Mr Muthoga acted like he was resuscitating him.

“The vehicle came to a stop next to where Karimi lay. A huge white man got out. He did not pay attention to Karimi but instead, he shouted at me, asking me how dare I stop his vehicle. Scared, Karimi ran in one direction, and I ran in another. Later in the night, as I pondered on this incident, I became angrier at the white man’s lack of concern. Karimi could have been genuinely sick, yet the man was unwilling to help take him to the hospital,” writes Mr Muthoga.

“It was then that I vowed to myself that I would study hard, become a judge, and then have the man brought before me in court, after which I would sentence him to death for his cruelty. The death sentence was very fresh in our minds. Just a few weeks before, Dedan Kimathi, the celebrated Mau Mau freedom fighter, had been sentenced to death by the colonial government,” he adds.