Grieving mourners during the burial of Tom Mboya, the assassinated Kenyan Cabinet Minister, at his father's homestead on July 12, 1969.

Fifty-five years after the assassination of Cabinet minister Tom Mboya, and his killer sentenced to hang, mystery still shrouds the murder with lingering questions on the motive and involvement of powerful figures.

For years, Isaac Nahashon Njenga Njoroge, who was condemned for the July 5, 1969, assassination, has been the only direct link to the murder that many believe altered the course of Kenya’s history forever.

But even with the passage of time, new revelations continue to emerge about the high-profile killing that rocked president Jomo Kenyatta’s government and scrambled his succession over the next decade.

Nation investigations reporter Duncan Khaemba has for the last eight months walked down memory lane to piece together the puzzle about the death of a man who has simply refused to be forgotten more than half a century later.

And for the first time, a man who claims to have been one of the hitmen in the murder plot has finally spoke out at the age of 92.

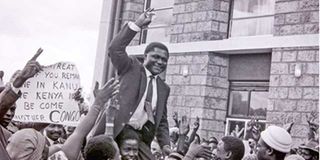

Tom Mboya is greeted by a jubilant crowds after the elections in 1963.

Ndwiga Muruathika from Embu claims they were three hitmen, including the man who was ultimately convicted for the murder of the charismatic politician.

On that fateful Saturday, Mboya had been driven from his home at Covent Drive in Nairobi’s Lavington Estate, in his official vehicle, a Mercedes Benz saloon registration KME 627.

The Economic Planning and National Development minister stopped briefly for breakfast at Panafric Hotel along Valley Road.

Thereafter, he had been driven to his office at Treasury building in the city centre.

From here some minutes past 1pm, Mboya had parted ways with an aide and his police driver, then driven himself out of the basement parking.

His car had pulled up outside Chani chemist on present-day Moi Avenue, which was then known as Government Road.

He had earlier placed a telephone call so he was expected at Chani chemist.

Inside the shop, Mboya chatted with the shop owner, Mrs Mohini Sehmi, a family friend, and bought his stuff.

Unknown to him, he was being trailed by the three men.

They were among Kanu youth wingers who represented their respective regions and were personally known to Mboya since he was the party’s secretary general.

As he walked out of the chemist, two shots rang out.

Kenya’s first Cabinet minister for Justice and Constitutional Affairs died at the age of 39, barely a month to his 40th birthday.

“That morning Mboya had ordered some prescription from Chani chemist, so somebody must have tapped his call. There were no mobile phones those days so his office line must have been tapped and they had listened in on his conversation ordering his medicine from Chaani. The only institution that had the technology to tap wire telephone was the Special Branch,” says Muturi Kigano, a former Kangema MP.

Kigano, 78, was starting off his law career when Mboya was killed. He first vied for the Kangema parliamentary seat in 1974, aged 28, and contested in every other election, apart from 2007, when he served as an officer in the defunct electoral commission of Kenya.

Kigano was only elected to Parliament in 2017 after 43 years.

Cotu Secretary General Francis Atwoli says there were suspicions about the assassination plot.

“This fateful day, Mboya was called and convinced to leave his body guards at home. When Michael Arum (an assistant commissioner of police) heard that he had left his Lavington home without body guards, he called Pamella (Mboya’s wife) making noise that Mboya might not come back home alive,” says Atwoli.

Atwoli, 75, was aged 20 when Mboya was killed. As a student at St Mary’s Secondary School, Machakos, a lecture by visiting Mboya had fired up Atwoli’s zeal to join the trade union movement.

At 21, Atwoli was elected the Nairobi Branch Secretary of Union of the Posts and Telecommunication Employees, which set him on the path to the helm of Cotu decades later in 2001.

Atwoli claims Mboya and then Attorney General Charles Njonjo had an appointment because they used to show up at the same location unaccompanied once in a while, but that Saturday Mboya did not know that it was a set up.

“Chani pharmacy used to import good perfumes for both Njonjo and Mboya,” Atwoli says.

President Jomo Kenyatta, Tanzania President Julius Nyerere and Tom Mboya engage in a light banter at the Nairobi Airport on March 30, 1968.

The shooting brought business to a standstill and news of the assassination spread fast and furious, shaking the country and the fraternity of newly independent African countries.

Legendary photojournalist Mohamed Amin captured events as they unfolded- from the scene of crime, inside the ambulance as an injured Mboya was rushed to Nairobi hospital and the hospital bed as medics attempted to save his life without success.

Njenga was swiftly identified as the main suspect, arrested, arraigned in court and sentenced to hang in a hurried trial.

Some have disputed whether the Bulgarian-trained sharp shooter was hanged at the Kamiti Maximum Security Prison. Questions have also been raised as to the real mastermind(s) of the assassination.

Just who was the ‘big man’ that Njenga referred to? And who wanted the youthful charismatic minister dead?

A ruthless Kanu operative, Mboya had been at the heart of the differences that saw his nemesis in Luo Nyanza Jaramogi Oginda Odinga quit government in a huff.

However, Mboya’s tribulations would begin in June 1968 after President Kenyatta suffered a stroke. It’s a development that sparked a vicious power struggle among Kanu big shots seeking to influence his succession.

A year earlier, a committee had been established to explore an amendment to a law crafted by Mboya and AG Njonjo in 1964 that provided for election of a successor for the remainder of the term if the president died in office.

It had been feared that the witty and charismatic Mboya would sweep into power effortlessly unless a scheme to block him was deployed.

According to David Goldsworthy who authored the book, Tom Mboya, the Man Kenya Wanted to Forget, the government introduced a constitutional amendment Bill providing that if the president died, the vice president would automatically succeed him. At the time, the vice president was Daniel Moi.

But MPs refused to pass the Bill in March that year.

Still determined to clip Mboya’s wings, Njonjo — backed by powerful figures who included Minister of State in the Office of the President Mbiyu Koinange and Defence minister Njoroge Mungai — presented a revised version in April under which the vice president would assume power for six months then a national election would be held.

The group had apparently held a private Kanu Parliamentary Group meeting in March 1968 in Gatundu where Njonjo apparently made serious allegations against Mboya.

He had claimed that he was eyeing Mzee Kenyatta’s seat with the help of his powerful American friends. But Agriculture minister Bruce Mckenzie dismissed Njonjo on the spot.

As debate raged in May, Mzee Kenyatta suffered a mild stroke, prompting Njonjo and Moi, without consulting Cabinet, to speedily come up with a third version that aimed at retaining the six months’ interim president but reduce his powers significantly.

But still Parliament declined to amend the Constitution with the final attempt being the addition of a new clause raising the minimum age of a presidential candidate from 35 to 40 in order to lock out Mboya. He was 39 at the time.

This, too, failed spectacularly leaving the team furious. But the group that came to be known as the “”Kiambu Mafia” was determined to retain power by all means. From then on, Mboya was a marked man.

“Mboya knew he was going to be assassinated. He talked to wazees here but the impression that he gave did not point directly to Kenyatta,” recounts Ochieng’ Oraya, Mboya’s neighbour in Rusinga Island, Homa Bay. Oraya was 19-years-old when the minister was shot dead.

“The main question you should ask yourself is why would Kenyatta kill TM? What was the motive? He wasn’t going to succeed himself. This boy was formidable, Njonjo and his group could not outwit him,” says Kigano, who would later be at the forefront of the fight for multiparty democracy that was achieved in 1991.

And according to Kigano, Njonjo had the intelligence machinery at his disposal through spy chief James Kanyotu.

“Kanyotu was heavily controlled by Njonjo. That is why Njonjo and police commissioner Bernard Hinga didn’t get along. He (Njonjo) didn’t want independent persons,” says Kigano, adding the AG literally bought loyalty. “He would buy them even cars from DT Dobie (a motor vehicle dealership). I know one instance when a client of mine confided in me he was told to go pick a Mercedes 280.”

Jomo Kenyatta (left) and Tom Mboya attend the Lancaster House Conference in London.

He adds: “Mboya was appealing to all Kenyans. He had become macho ya Kenyatta (eyes of the president) and his biggest confidant other than Mbiyu Koinange (who was also the President’s in-law),”

Atwoli says Mboya was very gifted and even before before reaching 30 years, he was meeting the likes of Pan-Africanist Kwame Nkurumah, who became Ghana’s founding president.

“He had established his own links with the Kennedy family in the US, which enabled him to run the airlift (scholarships) programme. With his moderate education, he did wonders. Some of us knew he could not live longer. He was a threat to many.”

“One of the districts then, Kiambu, had the president, Finance minister, AG, Internal Security minister and Foreign Affairs minister. The Central Bank Governor was also from Kiambu. They felt they owned the system,” says Peter Odede, Mboya’s cousin.

That Mboya was a big threat to those eyeing to succeed Kenyatta had been confirmed two months before his assassination. After the suspicious death of Argwings Kodhek in a road accident, a by-election was conducted in May 1969 for the Gem constituency parliamentary seat.

Mboya, being Kanu secretary general, was expected to lead campaigns for the ruling party as he was also the outfit’s point man in the region.

But he kept off, leaving the task of battling Jaramogi Oginga Odinga’s KPU party to Njoroge Mungai. As anticipated, Kanu suffered a humiliating defeat. Mboya had spoken without speaking.

There have been many versions on the circumstances under which the influential Cabinet minister was gunned down.

Before his assassination, Mboya had travelled to Ethiopia for a week-long meeting of Africa economic ministers. He was reportedly aware his life was in danger. Some of his associates prevailed upon him to seek political asylum but he is said to have dismissed this suggestion.

From Addis Ababa, Mboya had the option of proceeding to London for another official engagement but he chose to travel back to the country on Friday, July 4.

“While he was in Addis, the plan to kill him had already been hatched. The question was ‘how will we get him?’ They tried to get him at JKIA (Jomo Kenyatta International Airport) but they couldn’t because then assistant commissioner of police Michael Arum and the CID director teamed up to ensure he was not harmed. The Friday assassination plot failed but they made sure they would stop him from visiting Kenyatta in Gatundu,” Atwoli says.

When the plot to kill Mboya at JKIA aborted, the masterminds switched the plan to Saturday, July 5. The assassins were under firm instructions to ensure Mboya was eliminated that day to prevent him from leaving the country for London the next Sunday.

As fate would have it, the besieged minister dropped his guard when it mattered most, when he left his Lavington home that morning without bodyguards.

“He had official and unofficial security detail. That day there was going to be a match between AFC and Gor Mahia. He released the security detail to go home so that they would meet at the stadium,” says Peter Odede, Mboya’s cousin.

It would appear even in death, Mboya’s shadow loomed large over the nation’s politics. Reports indicated after the 1971 failed coup in which military chief Maj-Gen Joseph Ndolo and Chief Justice Kitili Mwenda were implicated, Njonjo silently placed Mboya’s widow Pamella under house arrest without President Kenyatta’s knowledge. Mzee Kenyatta would later chide Njonjo when he learnt of the restrictions on Pamela.

When Njonjo died in 2022, Kigano claimed it was the former AG who planned the killing of Mboya and facilitated the tapping of all his communication channels to monitor him.

“From what I gather, Njenga was just a mule. The fellow who shot him was a special branch marks man. He was waiting in a Mercedes. As soon as he shot him, he gave the gun to Njenga and drove off,” Kigano says.

“I am told Njonjo presented the fellow to Kenyatta boasting ‘this kijana Mboya wanted to overthrow you but we have scuttled that scheme. This is the boy we used to eliminate him.’ It’s said Kenyatta shed tears when he heard Mboya had been killed. Kenyatta asked them to leave the assassin with him and he gave instructions that the gunman be killed the way he had killed Mboya. Njenga was a fall guy, he was promised money by Njonjo,” Kigano alleges.

At the time of Mboya’s killing, Oraya was living in Nairobi’s Muthurwa estate and witnessed dramatic events as they unfolded.

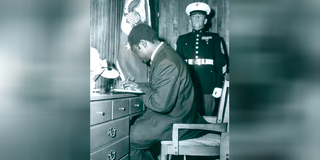

Tom Mboya, the Economic Planning Minister, signs the book of condolences for the family of Senator Robert Kennedy at the US Embassy in Nairobi.

“One of Mboya’s bodyguards, Otieno Fred, came and broke the police cordon, got into hospital and then came out announcing ‘Tom is dead. The body has been taken to city mortuary’.”

Vice President Danel Moi addressed the anxious nation.

Oraya, who was living with his uncle, George Migure, recalls the sombre mood at home.

“When we returned home that evening, Migure didn’t allow any lighting in the home. He said ‘our light is gone. Hakuna kuwasha moto.’ No cooking took place in the home. It was dark,” he recalls.

Tension gripped the country. Mboya was the second politician to be assassinated within the short period of Kenya’s independence after the murder in 1965 of another politician Pia Gama Pinto.

A decision was made to hurriedly bury Mboya. The funeral was held within one week in order to deflate the tension, which climaxed during the requiem mass at the Holy Family Basilica in Nairobi.

President Kenyatta’s administration came under attack, the memorial service turned chaotic and ended in disarray.

“I remember when Jeremiah Nyaga came to the Lavington home, people surrounded the vehicle prompting Mboya’s widow to intervene saying this is our friend,” Oraya recounts. With mounting anger, most government officials skipped the State burial at Rusinga Island.

Cooperatives minister Masinde Muliro attended as well as Jaramogi who was already out of government.

“Masinde Muliro was brave. The other person who came was JM kariuki,” adds Odede.

After Mboya was buried, Njenga, the prime suspect in the murder, was arrested in Nairobi. He was subsequently charged in a hurried court case that raised many questions.

“The trial was hurried. Even the evidence tendered was suspect. The scene where the gun was recovered was so choreographed. The gun was retrieved before Njenga’s arrest,” says Kigano.

Questions have been raised about Samuel Waruhiu, the High Court advocate who represented Njenga during the trial.

According to a Daily Nation report, Waruhiu claimed he was approached by Njenga’s wife to take up the case.

But Kigano disputes this.

“I know for a fact that Waruhiu was hired by Njonjo. He was instructed by Njonjo in his office to represent Njenga. He paid legal fees upfront in cash that he carried to his Electricity House office. He was not perturbed by his client being sentenced to death. In his last interview with Daily Nation, he refused to divulge who had instructed him to handle the case. Why didn’t he say it is Njenga who instructed him? Money was moved from Sheria House to Electricity House in a bag. A friend of mine, now a senior counsel, who was undertaking pupillage at Waruhiu firm, carried the money,” Kigano reveals.

Another controversy was whether Njenga was hanged.

Tom Mboya at a political rally. He was shot dead on July 5, 1969 along Nairobi's Government Road (Moi Avenue).

At the time, Mugirango West MP George Morara while on a parliamentary trip to Lusaka, Zambia, claimed to have spotted Njenga at an entertainment joint.

When the committee returned to Kenya, the MP gave the government an ultimatum to tell the country where Njenga was. But he died a few days later in a suspicious road accident in western Kenya.

But Kigano insists Njenga was hanged and other theories are misleading.

“When he was sentenced, he started talking in prison. He spoke freely how he was given 100 bob thinking he was going to be given a lot of money after killing Mboya. Let’s not have illusions, Njenga was hanged in Kamiti and his wife called to pick the clothes. Surprisingly, under prison rules, the family is supposed to be notified 24 hours before the hour the convict is hanged, but they were not informed of the hour of hanging. He was hurriedly executed because he had started talking and naming Njonjo as the fellow who had hired him,” Kigano claims.