Traders have resisted the new alcohol control rules.

Kenya’s battle with alcohol regulation has spanned decades. But despite the laws, the impact remains strikingly limited, and the recent uproar over the new policy by the National Authority for the Campaign against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (Nacada) reveals why.

The industry, which currently generates over Sh370 billion, over Sh50 billion in excise duty paid to the taxman, and employs over 300,000 people directly, has reacted with fury.

The new proposed rules—backed by Interior Cabinet Secretary Kipchumba Murkomen—are in the National Policy for the Prevention, Management and Control of Alcohol, Drugs and Substance Abuse.

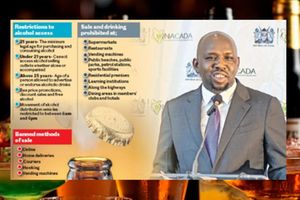

It, among others, raises the legal drinking age from 18 to 21, ban sale of alcohol in supermarkets, through online deliveries, and in public transport spaces, as well as compel alcohol manufacturers and distributors to contribute financially to the treatment and rehabilitation of individuals harmed by their products.

But the new proposed rules are just one in the many attempts to tame the industry.

Even though there have been laws tracing back to the colonial era, one of the most consequential recent rules is the 2010 Alcoholic Drinks Control Act — famously known as the Mututho Law after its proposer, former Naivasha MP John Mututho — to tackle rising alcohol abuse. It imposed licensing procedures, restricted sale hours, and aimed to curb youth consumption.

A 2012 study by the University of Nairobi on the effect of the Alcoholic Control Act (2010) on Nairobi residents, suggested a temporary reduction in binge drinking and greater compliance. However, these gains vanished as residents shifted to unlicensed venues or illicit brews, and enforcement agencies struggled to keep pace amid corruption and resource constraints.

Over time, authorities lost momentum and the law’s impact faded dramatically. Additional studies in a Nacada journal later identified systemic obstacles: poor coordination between national and county bodies, inconsistent enforcement, and underfunding across key agencies. Many counties lack functional Alcoholic Drinks Control Committees, which are essential for enforcing licensing and public education. Without them, illegal bars operate unchecked while rehabilitation and harm reduction programmes fall through the cracks.

Among its most radical proposals is raising the minimum age for purchasing, handling, consuming and selling alcohol from 18 to 21. It recommends banning alcohol sales in supermarkets, online platforms, restaurants, public beaches, recreational facilities, toy shops, residential areas, via home deliveries or vending machines. The policy also proposes a mandatory 300-metre buffer between alcohol outlets and schools, stricter licensing tied to full tax compliance, and bans on celebrity or sports personality endorsements, sponsorship of events, and outdoor branding near schools or living areas.

The industry’s reaction has been fierce.

Associations representing pubs, restaurants, retailers and brewers, including Pubs, Entertainment and Restaurants Association of Kenya (Perak), Alcoholic Beverages Association of Kenya and Retail Trade Association of Kenya, warned that over 1.3 million jobs in the alcohol value chain are at risk, from farming and manufacturing to hospitality.

Perak Chairperson Michael Muthami famously remarked, “They’re burning the house to kill the rat,” questioning the logic of the proposed age increase and bans on online or supermarket sales.

Some retailers stressed that up to 14 percent of their revenue comes from alcohol sales, and that a ban would disrupt supplier contracts and inventory cycles. The East African Breweries Ltd cautioned that curbs on e-commerce, developed during Covid-19, would undercut revenues and potentially drive more consumers to unregulated black markets.

Nacada, sensing the backlash, retreated. Its CEO Antony Omerikwa emphasised that none of these measures are yet law. The document, launched on July 30, 2025, is a policy framework, not an enforceable statute, he said, and assured the public that future steps will include legal and regulatory review. The Authority’s boss also said that public participation will be central to the process before any regulation becomes binding.

Yet this clarification has done little to appease critics, who argue that the scale of proposed restrictions, banning sales in restaurants, curtailing advertising, outlawing promotions and restricting endorsements, makes the policy untenable for businesses already operating on tight margins.

Underlying these tensions are long-running failures in regulation.

Despite the industry’s significant fiscal contribution, Sh51 billion in excise duty in 2023 and Sh366 billion in total revenue, manufacturers often still have to grapple with illicit and counterfeit alcohol, which still make up an estimated 50 to 60 percent of the market.

Many counterfeit beverages contain harmful toxins like methanol, putting public health at risk.

A November 2024 report by the National Crime Research Centre exposed how enforcement remains fragmented, overlapping agencies duplicate effort, and local political interests often shield illegal operators. Crackdowns are often electoral-era window dressing, with little follow-through. Even after the 2010 Act, local studies showed that illicit bars proliferated in informal settlements, and under-funded enforcement agencies lacked capacity, allowing unlicensed outlets to re-emerge rapidly.

The 2023 Alcoholic Beverage Sector Deep Dive report by the Kenya Association of Manufacturers (KAM) underscores how the regulatory environment itself hampers meaningful change.

Currently, more than six different ministries and agencies, from the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Investment to the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA), Weights and Measures, Nacada, and County Governments, hold overlapping or poorly defined responsibilities.

The result is a maze of conflicting rules, erratic enforcement, and costly compliance processes.

As it is, manufacturers and retailers are required to obtain multiple permits, while policy shifts like sudden excise hikes happen without consultation. This has created uncertainty that discourages formalisation and leaves room for illicit traders to thrive.

The new policy, critics say, repeats these mistakes by being too top-down and prescriptive. While well-meaning, they argue, it risks criminalising legitimate businesses rather than curbing harmful consumption.

Proposals to outlaw endorsements, celebrity advertising and brand activation events strike at the heart of the marketing model for alcohol brands, yet offer no alternatives. In banning alcohol at restaurants or online sales, without clear plans for enforcement or transition, the state may inadvertently push moderate drinkers toward dangerous brews. Already, cases of methanol poisoning and fatalities linked to illicit liquor continue to be reported across counties, particularly in low-income areas where legitimate products are out of reach.

Many stakeholders have expressed frustration over the apparent lack of consultation. Mr Muthami of Perak questioned why businesses were only shown the document after it was launched, despite its potential to dismantle key parts of the hospitality sector.

“The government must remember we are not the enemy, we employ thousands and contribute to the economy,” he said.

Retailers argue that consumer habits, developed during the pandemic including online ordering, cannot be undone overnight. They say technology should be regulated, not banned. Traceability systems such as barcodes or digital age verification could enable safe online sales. Meanwhile, producers like the East Africa Breweries Limited and Keroche have called for incentives to ensure compliance instead of sanctions that force them to the margins.

But for Nacada, the stakes are higher. Surveys it has taken in 2023 and 2024 indicate alcohol abuse in Kenya remains a public health crisis. In counties like Murang’a, Embu, Kisii, Kirinyaga and parts of the Rift Valley, Nacada has linked excessive drinking to social collapse, rising crime, broken homes, school dropouts, gender-based violence and economic stagnation.

To remedy this, Nacada sees the policy as a roadmap to prevent a full-blown addiction crisis. Dr Omerikwa said during the launch that, “This policy is a living commitment to the Kenyan people and not just a technical document.”

He also clarified that the 21-year age threshold applies only to the sale and consumption of alcohol, not the constitutional age of consent, which remains 18.

Critics, however, say that by focusing on criminalisation and sweeping bans, the policy fails to address the underlying causes of alcohol dependence. Poverty, joblessness, untreated mental illness and trauma remain the biggest risk factors, yet there are a few state-supported addiction treatment centres or economic reintegration programmes. For this lot, laws alone cannot cure what is fundamentally a socio-economic problem.

The stakeholders in the sector agree on one thing, that the government should resort to a more balanced approach which includes: increased public education to demystify alcohol risks, youth empowerment through entrepreneurship and skills training, and rehabilitation funding for counties with high dependency rates.

For retailers, better coordination between agencies and a unified digital licensing platform could plug enforcement loopholes and allow legal operators to thrive.

For now, the fate of the policy hangs in the balance. If Nacada follows through on its pledge to open the process to dialogue and align implementation with business and community realities, the policy may evolve into a progressive blueprint.

But if the government pushes ahead without consensus, it risks repeating history, a cycle of laws that are passed with great fanfare but unravel in the chaos of Kenya’s fractured regulatory landscape.