ODM leader Raila Odinga and President William Ruto.

For more than four decades, former Prime Minister Raila Amolo Odinga was a constant in Kenya’s political story.

In him, his loyalists saw a man whose life intertwined with the nation’s own struggles for democracy, justice, and inclusion.

Mr Odinga’s name, they say, was synonymous with resistance, resilience, and reform.

His journey — marked by exile, imprisonment, power, betrayal, and redemption — defined the shape and spirit of Kenya’s post-independence politics.

Born on January 7, 1945, in Maseno, Mr Odinga was the son of Kenya’s first Vice President, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, one of the architects of the independence struggle.

Educated at Maranda High School and later in East Germany, where he studied mechanical engineering, Mr Odinga returned home in the early 1970s to teach at the University of Nairobi.

But he soon discovered that his calling was neither confined to classrooms nor factories. It lay in confronting a political system that stifled freedom.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, then President Daniel arap Moi’s regime had become synonymous with repression.

The Odinga family was a marked name, and Mr Odinga’s involvement in underground movements pushed him into the crosshairs of state security.

After the 1982 attempted coup, in which rebellious soldiers sought to overthrow Moi, the slain ODM leader was arrested and detained without trial for six years.

Former Prime Minister Raila Odinga and former President Daniel Moi in Nairobi on July 8, 2012.

He would later claim that he was accused of involvement merely because of his association with pro-reform activists and his father’s political stance.

For Kenyans, his name became shorthand for courage. For the state, it became a threat.

When he was finally released in 1988, Mr Odinga would later be re-arrested two years later for supporting the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD) — a movement demanding multiparty democracy.

Detention, torture, and intimidation could not break him.

When Kenya finally reintroduced multiparty politics in 1991, Mr Odinga would emerge as one of the faces of change, standing beside his father in FORD. But as with many liberation movements, unity proved elusive.

After Jaramogi’s death in 1994, Mr Odinga inherited both his father’s political mantle and the divisions that came with it.

In 1997, he made his first run for the presidency on the National Development Party (NDP) ticket, finishing third behind Moi and Mwai Kibaki.

He managed 667,886 (10.79 percent) against Mr Kibaki’s 1,911,742 (30,89 percent) and Mr Moi’s 2,500,865 (40.40 percent).

That contest, though unsuccessful, cemented him as a national figure and revealed a politician capable of transcending regional boundaries.

Then came one of his most audacious moves: joining hands with Moi, the very man whose government had once jailed him.

In 2001, Mr Odinga merged NDP with KANU, taking a Cabinet post as Energy Minister. Many viewed the alliance as a betrayal, but he described it as strategic and an attempt to reform KANU from within.

But when Moi named Uhuru Kenyatta as his successor in 2002, he openly rebelled.

He walked out with other disillusioned KANU stalwarts to form the Rainbow Alliance Coalition (NARC) that swept Mwai Kibaki to power in a historic election.

His role in the NARC victory was decisive. He mobilised grassroots support, united fractious opposition groups, and turned the “Kibaki Tosha” declaration into a national rallying cry.

But soon after, the honeymoon soured.

Disagreements over power-sharing, constitutional reforms, and patronage left him feeling betrayed. He accused Kibaki’s inner circle of sidelining him and reneging on the MoU that had guided their coalition.

His 2022 presidential running mate Ms Martha Karua, the People’s Liberation Party (PLP) leader, recalled during a recent interview with Daily Nation how Mr Odinga was locked out of State House by Kibaki’s inner circle.

She recalled how she made a frantic call to Mr Moody Awori, a senior figure in the opposition National Rainbow Coalition (Narc) that formed the government in 2003.

Ms Karua was worried that a simmering power struggle was unfolding away from the eyes of Kenyans, who were still in an ecstatic mood after Narc ousted the authoritarian Kanu from power after 40 years.

A disagreement between President Kibaki and Mr Odinga over the formation of the cabinet, as agreed before the elections, dampened the celebrations just days after the landmark victory in the December 2002 polls.

“Right from day one, on the appointment of cabinet, there was a disagreement between Raila and Kibaki despite coming to power as a united entity,” Ms Karua, who had a front-row seat to the unfolding power play in the new administration, recalled in a recent interview.

On Wednesday, she recalled how Mr Odinga bore immense personal sacrifice, spending years behind bars and away from his loved ones in pursuit of freedom for all Kenyans.

“Raila's illustrious career, spanning decades, towers like a colossus across Kenya and the African Continent. His life was a testament to courage, endurance, and an unwavering commitment to the liberation and transformation of our nation. Few lives have been so fully devoted to the cause of justice and democracy,” said Ms Karua.

Following the 2003 Narc fallout, by 2005, Mr Odinga had reinvented himself again — leading the “No” campaign in the constitutional referendum, symbolised by the orange that later birthed his Orange Democratic Movement (ODM). The referendum’s outcome — a government defeat — made him the de facto opposition leader once more.

The 2007 general election was perhaps the most defining — and traumatic — moment of Mr Odinga’s political career.

Running against President Kibaki, Mr Odinga’s ODM appeared to be cruising to victory. But when the Electoral Commission abruptly declared Kibaki the winner, violence erupted nationwide.

More than 1,000 people were killed, and hundreds of thousands were displaced in the chaos that followed.

It was the darkest chapter in Kenya’s post-independence history — a moment that forced the country to confront its ethnic and political fractures.

International mediation led by Kofi Annan birthed the Grand Coalition Government, with Kibaki as President and Mr Odinga as Prime Minister. For the first time, Kenya had two centres of power — an uneasy marriage that both stabilised and strained governance.

Former Prime Minister Raila Odinga and former President Mwai Kibaki.

The partnership was marked by both achievement and tension. Mr Odinga was credited with reforms in infrastructure, civil service, and anti-corruption efforts. Yet he often clashed with Kibaki’s allies, particularly over Cabinet decisions and appointments.

At one memorable government retreat in Mombasa, frustration boiled over — the “Nusu Mkeka” moment — when he protested over alleged mistreatment in government despite being the Prime Minister.

When the coalition ended in 2013, Mr Odinga once again took his battle to the ballot.

The new Constitution had redefined Kenya’s political landscape, introducing devolution and an independent electoral body. Mr Odinga, then, ran under the CORD coalition, facing off against Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto, who had formed the Jubilee Alliance.

The election was close, but the Supreme Court upheld Kenyatta’s victory.

Mr Odinga accepted the verdict, but his supporters remained convinced he had been robbed. The theme of “stolen victory” would haunt his subsequent campaigns.

Mr Kenyatta on Wednesday recalled their journey from “fierce political opponents to partners in the pursuit of unity.”

“He was a formidable opponent, but he was an even more invaluable ally in the cause of reconciliation,” the former president said.

He described Mr Odinga as a “patriot driven by an unshakable belief in justice and peace.”

In 2017, like in 2013, history repeated itself.

Mr Odinga, then leading the NASA (National Super Alliance), challenged Kenyatta again.

The election was annulled by the Supreme Court due to irregularities — a landmark ruling in Africa. But when the repeat poll went ahead without major reforms, the former premier boycotted, claiming it was predetermined.

Then came another of his boldest moves — the January 30, 2018, swearing-in at Uhuru Park as the “People’s President.”

The act shocked the establishment and thrilled his base. It marked the peak of defiance — but also a turning point.

The famous handshake between President Uhuru Kenyatta and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga at Harambee House in 2018.

In March 2018, he stunned the country by shaking hands with President Kenyatta on the steps of Harambee House.

The Handshake ended years of hostility between the two and ushered in a period of relative political calm.

It birthed the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), a reform agenda meant to heal the nation’s divisions.

But critics accused the process of entrenching elite power-sharing and undermining democracy. When BBI collapsed at the courts, Mr Odinga’s alliance with Kenyatta began to wane.

Still, the Handshake redefined his image — from a street protester to a statesman working across the aisle. It also set the stage for his final presidential bid in 2022, backed by the State under the Azimio la Umoja One Kenya coalition.

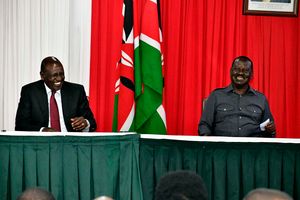

President William Ruto and Raila Odinga at State House, Nairobi on August 27, 2024.

When the results were announced, William Ruto — Odinga’s former ally-turned-rival — was declared the winner.

Dr Ruto narrowly won in the first round, securing 7,176,141 votes (50.49 percent) against Mr Odinga’s 6,942,930 votes (48.85 percent) in the results announced by then Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) chairman, the late Wafula Chebukati.

Mr Odinga once again disputed the outcome but accepted the Supreme Court ruling that upheld Dr Ruto’s victory.

Many thought that would mark his retirement. But he refused to fade quietly. He continued to lead protests against what he termed government illegitimacy and economic injustice.

By 2023, he had re-emerged as a continental figure — endorsed by Kenya and the East African region for the African Union Commission chairmanship, signalling a shift from domestic politics to diplomacy.

“Raila Odinga’s story was not just political; it was generational. He represented continuity in Kenya’s unfinished struggle for justice. To his admirers, he was the conscience of the nation — a man who fought for democracy at great personal cost. To his critics, he was an eternal agitator who thrived on populism and grievance,” quipped advocate Chris Omore.

Yet few could dispute his influence.

The ODM leader-built movements and inspired loyalty across ethnic lines.

His political resilience, his ability to reinvent himself, and his unyielding charisma made him a fixture in Kenyan life.

His allies say he never became President, but he often acted like one — setting the agenda, defining debates, and forcing reforms that others later claimed credit for.

“His story is one of sacrifice and unfinished business; of a man who came close to power, yet whose real power lay in moving the nation’s conscience.”