Raila Odinga's bid for the African Union Commission Chairpersonship ended in defeat during the February 2025 elections.

Africa has had a terrible record dealing with extreme poverty. Adebayo Adedeji, the legendary Nigerian head of the United Nations Economic Commission of Africa, campaigned vigorously against the structural adjustment programmes imposed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank.

With facts and figures, he showed that these contributed poverty’s increase, and brought this record to global attention by memorably describing the 1980s as Africa’s “Lost Decade”. The continent’s economic growth had declined rapidly in that decade by an average of 2.5 per cent annually by 1990, hitting the already poor the hardest.

Hard as it is to believe, things have got much worse since then for the poor. In 1990, Sub-Saharan Africa accounted for 15 per cent of the world’s extremely poor. By 2022 that figure had soared to 60 per cent, while every other world region reduced poverty levels. The magnitude of the dramatic downward spiral has been felt by the extremely poor, with about 450 million scrambling every day to try to provide life’s basics for their families, not always successfully.

The African Union appears determined to change this sorry tale by appointing as the next Chairperson of the Africa Union Commission a visionary leader capable of setting in motion the “transformative change” promised in the Commission’s historic “Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want”. That Agenda has the unprecedented goal of achieving a “dignified standard of living” for all the continent’s people by its centenary year, or of course earlier. That goal would require, among other things, drastically reducing gaping inequality, which of course goes against the world’s prevailing market and ideological trends.

Transformative campaign

A simultaneous but more immediate goal is the Agenda’s flagship project, “Silencing The Guns in Africa”, pledges to bring an end to the continent’s own forever wars and conflicts that have taken a toll of millions and continue to rage with no prospect of end in sight. Somalia is the poster child of this crisis: there seems to be no effort underway to bring about peace, except the use of force that has failed to end the war.

Africa’s heads of states have been emboldened in their transformative campaign by some astonishing turn of economic and political events. Last year, the IMF forecast that in 2024, the world’s seven fastest growing economies, and 12 of the top 15, would be African.

This is a result of many factors, but primarily because the continent’s vast natural and mineral resources have emerged as an indispensable engine of growth for the increasingly hi-tech orientation of industrialised economies. The magazine, Foreign Affairs, captured these developments in a succinct headline: “The Global Economy’s Future Depends on Africa: As Others Slow, a Youthful Continent Can Drive Growth.”

Some of this new attention was in prominent evidence at the United Nations General Assembly’s high level “presidential” session which concluded recently. The United States announced it would push for two new permanent non-veto-wielding seats for Africa. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres emphasised that Africa should have veto power as well.

Africa’s youngest and newest leader, the dynamic prisoner turned President Diomaye Faye of Senegal, who is enjoying intense attention, asserted that the New World Order is essential for global stability, and the UN Security Council needed to give Africa veto power, reflecting the radically changed global demographics.

Africa is also being paid high level political attention in other forums. A year ago, the Group of 20 (G20), the premier grouping of the Global South and industrialized countries, made the African Union a permanent regional member at its New Delhi Summit. These are exceptional achievements for the AU Commission and have given Africa a seat at the table for the highest-level discussions where fateful decisions vital to Africa’s, and the world’s, future are made.

The breakthroughs have also begun re-shaping the continent’s despairing image internally and internationally. None of this, however, should in any way diminish the magnitude of the challenge ahead. Only a miniscule number of economically impoverished countries in our lifetime has managed to achieve exceptional growth as well as massive reductions in poverty and inequality. To strive for such an outcome for an entire continent, with 55 countries and 1.5 billion people at radically different levels of economic and social development, will be a daunting task.

Global profile

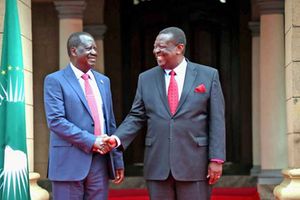

That task will take on new life with the election at the February AU summit of a new Commission chairperson. With this new transformative mandate, the Chairperson will become, or will need to become, a pivotal African and international figure, the global face of the African Union and of the African people. A loose comparison would be the UN Secretary General, who is the face of the United Nations as well as of all humanity. In that regard, with his well-known African and global profile, Mr Odinga will hit the ground running.

The two of us have worked at senior levels internationally, including at the United Nations under Secretary-General Kofi Annan, on many of the goals that are also at the heart of Agenda 2063. We have also had the honour to work closely with Raila, as he is known universally by presidents and peasants and workers alike. We have seen how effortlessly he moves from the highest levels of African and international leaderships, to spending time with street traders, women farmers and passionate young entrepreneurs and protesters.

This particular skill is one of his strongest suits for the Commission Chairmanship. In our view, one of the AU’s principal weaknesses is that it is not very well known in the grassroots and heartlands of the continent. That must change. The African Union should be seen as a beacon of hope and protection for the tens of millions caught up in strife, oppression or dislocation but feel forgotten by the rest of the continent. Sometimes they think the outside world cares more.

Mr Raila Odinga is the kind of person who will travel to ravaged areas to talk to the afflicted and do whatever possible to try to ease and understand their pain and launch efforts for their immediate relief. In addition, we believe Mr Odinga is uniquely qualified to serve as the new AU Commission Chair, given his long history as an instinctively transformative figure with the political and practical skills to translate visionary goals into successful policy.

Prime Minister of Kenya for five years as well as the enduring leader of the opposition for two decades till this year, Mr Odinga was also twice a Senior Envoy for the African Union on critical assignments. One of these was his five years as AU High Representative for Infrastructure Development, an area he presciently promoted from the 1990s onwards as the crucible of economic growth and industrialization of African countries.

Mr Odinga has presented to Africa’s leaders his ambitious, carefully thought-through agenda for this moment of historic transformation and transition. To achieve this agenda, it will require a leader who can mobilise and work seamlessly with the African leaders.

It will require great political stature and moral authority to mobilise the global community and to form important strategic partnerships globally and within Africa. Cometh the hour cometh the man. Mr Odinga is the man for this season — a man forged in the national and continental political cauldron for a time such as this. Africa would be very fortunate to have him at the helm of the African Union Commission at such a historic and an exciting moment.

Olara A. Otunnu has served as President of the UN Security Council, Chairman of the UN Commission on Human Rights, and UN Under-Secretary General and Special Rep for Children and Armed Conflict. Salim Lone, a widely published writer, was Spokesman for Mr Raila Odinga, Prime Minister of Kenya and opposition leader (2005-2013), and Director of Communications and Spokesman at the United Nations (1997-2003).