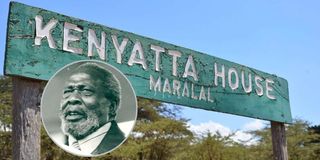

A signpost to Kenyatta House in Maralal, Samburu County, where Mzee Jomo Kenyatta spent the final days of his detention before Kenya’s independence.

The sudden re-emergence of Jomo Kenyatta’s name on the pre-independent Kenya political scene presented one of the biggest dilemmas for the colonial government.

They now had to court a man Governor Patrick Renison had described as an “African leader to darkness and death” by sending prominent settlers and politicians to act as a secret backchannel to him in order to understand his political outlook.

Perhaps the most senior British politician to secretly meet Kenyatta in restriction was Lord Antony Lambton, a British aristocrat and a Conservative member of Parliament, who flew all the way from England and spent three hours interviewing him at Maralal in 1961. According to a copy of the interview marked ”very private,” Lambton spent time seeking to know from Kenyatta whether he would evict white farmers to settle the landless Kikuyu, how he would deal with Jaramogi Oginga Odinga if he were to form a government, and even asked him whether he believed in God.

Governor Patrick Renison (left) and Jomo Kenyatta.

For starters, when Kenyatta was arrested at the beginning of the State of Emergency, the British resolved that no man should mention his name, and that it should appear as if he had never existed. He was a man condemned to political oblivion who was never to return even to his ancestral home at Ichaweri, where his house had been flattened.

Genuine sympathy

From then onwards, Kenyatta was on the verge of being forgotten politically until 1958, when Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, driven by his genuine sympathy for him and partly by his motive to curtail Tom Mboya’s political influence, shocked everyone in the Legislative Council when he declared Kenyatta as the political leader of Kenya.

At first, there was an appalled silence among members — including Africans such as Tom Mboya, Jeremiah Nyagah, Bernard Mate and Gikonyo Kiano — who were shocked by Odinga’s remarks. Although they were sympathetic to Jomo Kenyatta’s plight in prison, they never saw him as a future leader. And after they had recovered from their shock, they rushed to disassociate themselves from Jaramogi’s remarks, records show.

Political scene

But Jaramogi had already done the damage. From then on, Kenyatta’s return to the political scene became certain as his name became the clarion call for African unity and independence. Politicians such as Mboya, Kiano and Nyagah, who hitherto had been hesitant to endorse him as the leader of Kenyan Africans, had no other option but to jump onto the bandwagon out of fear of being labelled traitors.

Meanwhile, the wind of Black Nationalism that was sweeping across the continent had made the British cognisant of the fact that African rule in Kenya was inevitable. But Kenyatta was initially not an option for the British, since he had been accused of managing Mau Mau. Instead, they envisioned propping up an African government made up of moderate young Kenyan nationalists to protect British interests and the huge settler population that was to remain in post-independent Kenya.

But as the “release Kenyatta” campaign gathered pace with African nationalists insisting there would be no independence without Kenyatta, the British had to swallow the bitter pill of accepting him as the definite leader of Kenya. They secretly sent politicians, settlers and even envoys to talk to him in prison with the aim of understanding his political views and his thoughts on thorny issues that could affect their interests.

In the House of Lords in Britain, there was a fiery debate on this attempt to bring back Kenyatta to the political scene. The Earl of Albemarle declared, “One wonders whether the Colonial Office is really still in command in Kenya, because a group of foreign consuls were sent to visit this man. By whose acquiescence or instigation did these foreign consuls go and interview this man, an ordinary man without any special status?”

Another peer stated: “The man is a man of great magnetic personality, but he rules by fear. That has been proven over and over again.”

Overwhelming support

Lord Ogmore was, however, of the contrary opinion, stating, “If a man has the overwhelming support of his people, then he is a difficult man for both Her Majesty’s Government and the Government of Kenya to ignore. How can you ignore the views of such a man who has the overwhelming support of his people, especially when he is still detained by the Government of Kenya?”

The dilemma in which Britain found itself was evident in a letter written by the then British Prime Minister Sir Harold McMillan, who lamented, “We both feel anxious about Kenya. People are not yet accustomed to the idea that sooner or later, we shall have to accept independence in Kenya. From the Party's point of view, Kenya is going to create a big problem.”

The Kenyatta House in Maralal, Samburu County, on August 15, 2015.

Against this backdrop, Lord Lambton flew to Kenya and visited Jomo Kenyatta in restriction to understand his political stand and to attempt to strike a bargain between the settlers and the African nationalists.

“I saw nearly all the African leaders except Odinga,” Lambaton wrote. “I went to see Kenyatta in his little home at Maralal. The first thing that struck me was the extraordinary healthiness of his appearance. “

As the two settled down for the interview, Lambton asked Kenyatta whether he had a plan to become the leader of Kenya, and Kenyatta replied “I will do what my people want me to do.”

Lambton then asked, “I gather that it is likely that you are going to be offered the presidency of the shadow federation of Kenya, Tanganyika and Uganda. Will you take this position?” Again, again Kenyatta replied, “I am the servant of the people; it is as the will.”

As the interview picked up, Lambton shared with Kenyatta a plan for independence which he believed would give reassurance to the white settlers “upon whom the economy of the future depended”. According to his plan, the Governor would give internal independence to Kenya but retain powers, until he was certain that the new African Government had solved four main problems: the position of the Somalis in the North, the status of the Maasai, the status of the Coastal strip and the problems of title deeds. When Lambton asked him whether he thought the plan was reasonable, he replied, "It would be perfectly reasonable.”

Kenyatta went on to state that he would have no difficulty in solving the issue of the Somalis, Maasai and the coastal strip, because “all the Africans were Africans and could easily solve their problems by talking together.” On the issue of title deeds, he complained that he had always been misunderstood over the matter, revealing that it had never been his policy to drive the Europeans out, and that he realised their value to the economy.

The two delved into the thorny issue of land in the Mt Kenya region, which was in the hands of the White settlers, with Lambton asking Kenyatta whether he would confiscate European land and hand it to landless and jobless Kikuyus.

“Do you not think that with the landless and unemployed Kikuyu there will be great pressure put upon you to take land from the settlers and start a snowball of lack which can drive them out of the country?”

European farms

In his response, Kenyatta said that was a small problem because there was plenty of land in Kenya and the landless could be settled elsewhere.

“Where?” Lambton asked, and Kenyatta replied that Kenya is a huge country and there was no need to confiscate European farms to settle the landless.

Lambton then turned to the question of Jaramogi, who had taken a tough stand against colonialists, demanding that land should be returned to Africans without compensation, and had also established contact with Communist countries. Lambton told Kenyatta that he believed Jaramogi posed the biggest threat to any African government that was to be formed. According to Lambton, Kenyatta suddenly became angry. “His face at this moment completely hardened and he almost hissed at me, showing strong emotion,” he recalled in his recording of the interview.

“Odinga would be a problem in what sense?” a visibly agitated Kenyatta asked.

Lambton replied that he believed so because Jaramogi was unlikely to join any government that included Mboya and that he could form an opposition party that appealed to the traditional people who were many in Kenya.

Kenya's first Vice President Jaramogi Oginga Odinga.

“What do you mean?” Kenyatta asked, to which Lambton replied that Jaramogi “might appeal to the uncivilised emotion of the Africans, which still existed only just below the surface.” Kenyatta stated that it would be possible to deal with Odinga.

But Lambton did not stop there in his quest to sow a seed of discord between Kenyatta and Jaramogi. He asked Kenyatta whether as the head of government, he would take action against Jaramogi or any other political leader who might attempt to undermine the stability of the state. And Kenyatta replied that he certainly would. He then asked Kenyatta if he thought Jaramogi, with the support of Russians, could become “(Patrice) Lumumba of Kenya, instigate trouble and tribal warfare,” but Kenyatta replied, “We can deal with that problem when we come to it.”

Another question Lambton dwelt on was on Kenyatta’s spirituality, asking him whether he believed in God. Kenyatta replied, “Yes, but in a wide sense.”

“In What sense?” Lambton asked, and Kenyatta replied, “In the sense that he is the leader of all religions.”

Lambton then asked, “You mean that you are a Pantheist?” to which Kenyatta replied, almost with a relief on his face, which he was.

Intimidating personality

Other questions asked were whether Kenyatta as the leader of Kenya would accept technical aid and loan from Russia, to which Kenyatta replied that he would look into that carefully, and whether he believed there was a possibility of a United States of Africa, to which Kenyatta replied, “Yes, it will take a long time but all good things take a long time.”

In a report he wrote after the interview, Lambton couldn’t resist highlighting Kenyatta’s personal magnetism and intimidating personality, which left the Briton mesmerised.

“He is, without doubt, an amazingly compelling personality. His eyes are extraordinarily interesting. The left one is larger than the right, and the pupil appears to be surrounded by phosphorus. Twice while I was talking to him, I found myself becoming very slightly mesmerised and forgetting the next question that I was going to ask,” he wrote.

Although he observed that Black rule in Kenya was inevitable, he advised that it was coming too early and at the wrong time. “It would be very hard to imagine a more unfortunate time than the present to bring an African government into power.”

Mzee Kenyatta was eventually set free, became prime minister and later served as the founding president until his death in August 1978.