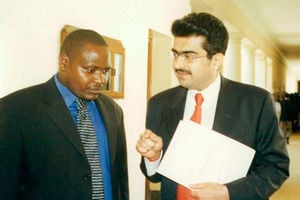

Kamlesh Pattni (second right) with Lybian Salah Ajin (right) and other traditional leaders at the installation of King Peter Mumia II of Wanga in Matungu.

On January 3, 2010, a State-owned Afriqiah Airways jet flew out of Jomo Kenyatta International Airport for Tripoli. On board was Kamlesh Pattni, poised for a high-stakes meeting with Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi.

Pattni, styling himself as the “Chairman of the House of Traditional Elders of Kenya”, had organised this diplomatic expedition thanks to his Libyan networks. He had handpicked an entourage of 600 “elders” representing various Kenyan communities. He positioned himself at the centre of cultural political power.

In the delegation was Maina Njenga’s Mungiki movement—by far the largest delegation—alongside Luo Council of Elders leader Riaga Ogallo, Maasai elder Daniel ole Muyaa, Njuri Ncheke’s Pharis Ruteere, Peter Mumia of the “Wanga Kingdom,” and Mwangi Thuita, the chairman of the Embakasi ranch.

By organising Kenya’s traditional power brokers, and taking them to Libya to engage with Gaddafi, Pattni was now shifting his influence to the African stage, where opportunities for business could open up. To an extent, this was his bid to spring clean his tarnished reputation and reinvent himself as a revered national figure.

The meeting with Gaddafi was a hurried exercise, and records show that the House of Traditional Elders was registered on December 22, 2009, some 10 days to the Tripoli trip.

During the first meeting, in which he met 160 Kenyan elders, Gaddafi promised to build 42 cultural centres in Kenya from which the elders would operate. In Libya, the elders had been given police escort to Corinthia Hotel and had a four-hour dinner with Gaddafi. They were welcomed to sumptuous meals of camel steaks, given $1,000 each for miscellaneous expenditure, handed expensive gifts, including Rolex watches, and urged to present their development needs in later meetings. In turn, they presented Gaddafi with a leopard skin—symbolising authority.

Goldenberg scandal

After soiling his image with the Goldenberg scandal, Pattni had tethered his ambitions to Gaddafi’s lofty dreams of a “United States of Africa”.

Gaddafi was positioning himself the leader of African elders and was engaging them through the various Libyan embassies in Africa. In Libya, he had managed to stay in power through the “cultural revolution”, with tribal elders holding the balance of power. Gaddafi’s dream was to create traditional power structures across Africa—loyal to him—and use Libya’s oil wealth to advance his vision of a “United States of Africa”. He was also pushing for a single African currency.

Before shifting to use elders, Gaddafi had in previous years—especially in the 1970s and 1980s—supported rebel movements. But as age and geopolitics caught up with him, he cultivated good relations with African leaders. Actually, former President Mwai Kibaki’s nephew, Alex Muriithi, was the first to make contacts with Gaddafi after Narc replaced Kanu in 2002. Since 1987, Kenya had closed the Libyan embassy after then President Daniel Moi accused the diplomats of plotting to overthrow his regime. It was reopened in May 1998, and it was here that Pattni would find another platform.

Though he had hobnobbed with politicians ever since he sold the Goldenberg mineral-export lie to Treasury, In 2006, Pattni resurrected the defunct Kenya National Democratic Alliance (Kenda) party, an entity originally founded by university lecturer Mukaru Ng’ang’a, a socialist. Brandishing lofty promises to uplift the livelihoods of ordinary Kenyans and champion equality, Pattni portrayed himself as a beacon of hope and not the “thief” he was described as by the commission of inquiry that was set up to investigate the Goldenberg scandal.

After Goldenberg, he had also made a dramatic spiritual flip—converting from Hinduism to Christianity, founding his own church, and adopting the moniker “Paul.” Armed with a political party, a church and later an elders’ lobby group, Pattni had one hurdle to jump: end the Goldenberg nightmare and get back the Grand Regency, the only investment he had in Nairobi. The Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) was still pursuing the Sh2.5 billion advanced to Uhuru Highway Development Limited.

The 13th floor of the Grand Regency was Pattni’s sanctuary even during the hotel’s receivership. This secretive haven, once patrolled by armed sentries, became the stage where Pattni entertained an eclectic mix of confidants, power brokers and international stakeholders. Among these were the Libyan buyers, whose presence added an enigmatic layer to the hotel’s legacy. In the plush confines of the office, negotiations unfolded, interests were piqued, and connections were forged—Pattni himself admitted to a parliamentary committee that he was well-acquainted with the Libyans. Yet, he left the timeline of their association tantalisingly vague.

Telling revelation

A noteworthy twist came in June 2007, when Kibaki embarked on a State visit to Libya. Among the agenda items was a telling revelation: Item six of the memorandum recorded Libya Africa Investment Portfolio’s expressed interest in investing in Kenya’s hospitality sector, with the Grand Regency prominently in their sights. How did the Libyans get to know that Grand Regency was on sale? This development deepened the mystery of the 13th floor, where whispers of high-stakes negotiations hinted at a larger geopolitical chess game.

If the Libyans were interested in Grand Regency, then Pattni had to be sweet-talked to drop all the time-wasting cases he had lodged in court against CBK. In March 2008, Kibaki was among the select dignitaries when Gaddafi inaugurated the Gaddafi National Mosque in Kampala, Uganda. Whether Grand Regency was discussed is not known, but the following month, April 2008, Pattni was granted amnesty from prosecution as long as he handed over Grand Regency to Central Bank.

“The hand-over of the hotel was meant to give him amnesty in respect of all civil and criminal cases against him and associated companies in respect of the Goldenberg saga,” a parliamentary committee investigating the sale of the hotel to Libya concluded.

This sale became so controversial that Finance Minister Amos Kimunya—he of the I would rather die than resign fame—was forced out. But still a commission of inquiry into the sale, meant to cover-up rather than shed light, found that there was no err in the sale.

With the Grand Regency handed over to the Libyans at a net sale price of $41 million that was deposited in the CBK Federal Reserve Bank Account in the US, Pattni moved to consolidate his networks in Libya.

In April 2010, following the Tripoli meeting, Pattni immersed himself into the intricate tapestry of Gaddafi’s grand projects. In Tripoli, the Kenyan delegation experienced a reception befitting royalty. Armed presidential guards ushered them into a fleet of luxury buses that whisked them away to the opulent Corinthia Hotel. Over the next few days, they were treated to a grand tour of Tripoli’s bustling cityscape. The pinnacle of their visit came on the third day when they were summoned to meet Gaddafi.

After this meeting, and to show his leadership acumen, Pattni orchestrated the crowning of Peter Mumia as the “14th King of the Kingdom of Wanga” in a spectacle shunned by key family members. This coronation, rife with controversy, served as a strategic platform for Pattni’s ambitions. In return for his patronage, “King Peter Mumia II” endorsed Pattni’s audacious bid to vie for the Westlands parliamentary seat. Pattni had invited Uganda’s Toro Kingdom Queen Mother, Best Kemigisa, and Libya’s Sala al Hajim to give Mumia’s coronation a veneer of international grandeur.

Plasma television

It was announced that Gaddafi had donated a plasma television, a laptop, and a desktop computer to King Peter Mumia as tokens of goodwill. The Njuri Ncheke had been promised money to build a new headquarters, while the Miji Kenda Council received a bulldozer for each of the nine clans.

While Pattni’s political gambit was a fanciful charade aimed at eclipsing the shadows of his scandal-laden past, it was also part of his new persona. Meanwhile, Gaddafi was already charting his next theatrical venture: a grand Forum for Kings, Sultans, and Mayors of Africa, slated for September 2011—a gathering that promised to amplify his vision of African unity. But this was not to be after an uprising to topple him started in February 2011.

With the killing of Gaddafi, and as Libya descended into anarchy, Pattni turned his eyes to Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe. In March 2012, Pattni flew to Harare to ostensibly hand over a black-and-gold robe said to have been once donned by the deposed Libyan leader. Pattni was introduced as the leader of Kenya’s House of Traditional Elders, and during his speech, he declared Mugabe the “natural successor” to Gaddafi’s mantle of Pan-African leadership. By this time, Zimbabwe was going through a foreign currency crisis and Pattni sold his Goldenberg project to Harare.

Pattni is now alleged to have used this traditional elders connection to get into Zimbabwe and later engage in gold and diamond smuggling. He is said to have bribed politicians in Zimbabwe and moving dirty money using his global business empire to launder it.

As Pattni told Al Jazeera, “when you work, you must always have the king with you, the president”. So with the death of Mugabe, Pattni’s businesses in Zimbabwe relied on the political support of President Emmerson Mnangagwa.

The US Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control and the United Kingdom’s International Corruption Unit have now blacklisted Pattni, alongside 27 other individuals and businesses based in Zimbabwe, for orchestrating a sprawling network of global gold smuggling and money laundering.

Over the years, Pattni has been the face of impunity. While his Zimbabwean operations mirror his earlier schemes in Kenya, which involved export incentive fraud and bribery, he was never prosecuted in Kenya; though the judge who terminated his case was found guilty of wrongdoing.

Whether Pattni’s blacklisting will slow him down is not clear. He is not only hydra headed—but extends his greed to new spaces.

@johnkamau [email protected]