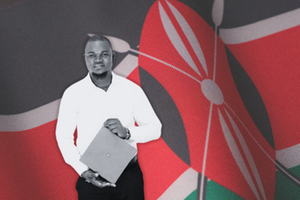

Mohammed Jarha arranging trays of dough ready for the oven at the Rimaya Bakery in this picture taken on August 11, 2025.

When Mohammed Jarha walked out of Hola Prison in Tana River County in April 2024, freedom tasted unfamiliar.

Eight months earlier, a judge had sentenced him to serve time after being found guilty of robbery.

Prison was supposed to break him but instead, it remade him.

Behind the grey walls of Hola Prison, Jarha had witnessed what life could become for a man who never changed course, old faces returning to the cells, harder and more hopeless each time, and he made a choice to never return.

“I left prison with a transformed mind. I wanted to be useful to myself, not a danger to society," he recalls.

But life outside had changed and opportunities were scarce.

Streets that once bustled with familiar faces were colder now and the rules of survival harsher. In this new reality, vigilante justice was the new law; only weeks after his release, he saw a suspected thief beaten nearly to death by an angry mob.

“The streets don’t give you time to explain,” Jarha says quietly. “You are caught, you are gone. No one waits for the police anymore.”

Determined to live honestly, he embarked on a gruelling job hunt, but months passed with no luck, until fate led him to Rimaya Bakery.

Mohammed Jarha arranging trays of dough ready for the oven at the Rimaya Bakery in Hola town.

Founded by a group of young men from different counties of Kenya, it was a safe space for people like Jarha who wanted to shed their pasts and learn honest trades.

The bakery’s founders pooled their meagre savings to buy mixers, ovens and ingredients to bake cakes and doughnuts which they supplied to shops and market stalls around Hola town.

In under a year, they had grown into a small but dependable enterprise supporting eight men and four women.

“Rimaya is more than bread and cakes. It’s about giving someone a second chance. We have trained young people who were on the edge, teaching them to bake, to earn, and to live decently,” says co-founder Andrew Okeng’o, who left Nyamira in search of work.

Landlady Fatuma Mayaa was one of their strongest supporters, renting them affordable space and admiring their work ethic.

The rent she collected from them paid for her disabled husband’s medication and kept food on her table.

“They have been here three years. No trouble, just hard work. They are the best tenants I have ever had,” she says.

But over the past month, the sweet smell of baking bread has been replaced by the stench of fear and extortion.

According to Jarha and his colleagues, a group of rogue police officers from Hola Police Station has turned the bakery into their 'personal ATM'.

“They started coming two weeks ago...They would walk in, demand cash and threaten to arrest us on strange charges if we refused,” Okeng'o says.

The bribes began as a daily Sh2,000, more than 70 percent of the bakery’s daily profit.

Then, last Friday, the officers escalated.

“They came in and took all the money we had made that day and left us with nothing to buy flour or sugar,” says Geoffrey Onyango, a father of two.

Weekly stipend

In two weeks, the group claims, the officers have extorted a total of Sh16,000.

Now, the demands have shifted to a weekly “stipend” to be sent directly, so the officers don’t have to come in person.

For Onyango, the loss has been devastating as his children’s school fees remain unpaid. The landlord is also threatening them with eviction. “I work 12 hours a day to keep my children in school. Now I’m failing them,” he says.

The landlady is also feeling the pinch. “My husband is disabled. This rent was our only steady income. Now, even food is not guaranteed. It is painful to see these young men, who are trying to do the right thing, being destroyed by people meant to protect them,” she says in an interview.

According to the bakers, resisting the officers only invites harsher threats of being framed for theft, possession of drugs or other fabricated crimes.

“They tell us it’s a fight we will never win. And in Hola, they might be right. Everyone knows some cops are untouchable,” Okeng'o says.

James Rashid, secretary-general of the local Civil Society Organizations Network, says the group’s ordeal is part of a wider pattern.

“These officers target vulnerable groups, youth, small traders, boda boda riders, people who can’t fight back, and their seniors know and in fact, they enable it by refusing to take action,” he said.

The network says it has filed formal complaints at the police station, but nothing has been done. They accuse the officers of turning the station into a “nest of corruption”.

“It is not just theft, it is economic sabotage,” Rashid says. “These young men were rehabilitating others, reducing crime, creating jobs. Now they are being pushed back into desperation.”

By last Friday, the group had decided to shut the bakery permanently.

With no capital left, no safety from police harassment and no way to meet their daily expenses, returning to their villages seemed the only option.

But the civil society network stepped in. They raised emergency funds to buy flour, sugar, and oil, just enough to resume small-scale production while pursuing justice.

But still, the damage is visible as the bakery has cut production by more than half.

“We are not done,” says Rashid. “We want the Independent Policing Oversight Authority (Ipoa) to investigate and surcharge the officers for the Sh16,000 they stole. They must pay for what they’ve done.”

Tana River sub-County Police Commander George Madolio did not dismiss the claims but noted that among many good officers, there could be bad ones, hence the need for further investigation.

"That matter has not reached my desk, but if it's indeed happening, then it’s very unfortunate and I will have to get to the bottom of it and also meet the affected so that we can help one another," he said.

He asked residents not to be coerced into giving bribes for whatever reason, noting that it proves one is liable to a criminal offense and could be buying their way into more crime.

Recruits in a parade during a past pass-out ceremony at Kenya Police College Kiganjo

He also notes that whereas the police will be blamed, intelligence reports show that crime has disguised itself and is currently using the most subtle businesses and activities to thrive.

“You may see someone hawking eggs and assume they are innocent, only to learn that they are the ones peddling bhang in large scale or even other hard drugs," he said.

For Jarha however, the experience has been a cruel reminder that walking the straight path is not always safe in Kenya.

“When I was in prison, I thought the danger was from criminals,” he says. “I didn’t know the danger could come wearing a police uniform.”

Yet, despite the fear, he refuses to give up.

“I have been to the bottom before. I’m not going back there,” he says firmly. “We will bake and prove them wrong.”