In March 1972, Queen Elizabeth made a short debut visit to Kenya and had lunch with President Jomo Kenyatta at State House, Nairobi, where she was bestowed the Chief of the Order of the Golden Heart.

In September 1975, Kenya’s first President Jomo Kenyatta threatened Britain with unspecified actions after the London-based Sunday Times implicated him and his family in a series of scandals, previously confidential documents reveal.

“The President has instructed the High Commissioner to stress that if the campaign against him continues in the British media, his government will consider taking effective measures to preserve and protect Kenya’s interest,” read a note verbale (a formal diplomatic communication) sent by Kenya to the British Secretary of State in September 1975.

Kenyatta’s rage was provoked by a series of articles published in the Sunday Times under the title ‘Kenya on the brink’. The scathing expose was written by John Barry, who alleged that the President and his family were engaged in corrupt activities and that he (Kenyatta) had prior knowledge of the plot to assassinate the flamboyant populist politician JM Kariuki.

In one article allegedly implicating the President’s family in poaching, Barry cited one Kenyan minister as remarking: “What can I do about it when he (Kenyatta) has just instructed me to issue a permit to export 15 tons of ivory to Margaret Kenyatta (the President’s daughter) and five tons to Mungai (Kenyatta’s nephew and Cabinet Minister).”

In another article, Barry claimed, “Coastal plot number 1700 in Mombasa land registry was once owned by Nyali Ltd, a public company whose shareholders seem to comprise mainly old ladies. On January 1, 1971, Nyali leased the plot to a small Nairobi textile company for £1,250 and annual rent of £20.

Two years later, on February 16, 1973, Nyali called in this lease. On June 25, the plot was sold freehold to Mama Ngina (the First Lady) for £500. (The sale was exempted from stamp duty). On the same day, Mama Ngina acquired the adjoining plots, 1701 and 1702.”

Barry alleged: “Two months later, on September 3, 1973, the president’s wife leased the three plots to African Tourist Development Corporation, despite its imposing name a private company whose largest shareholder is a Swiss concern. The price for the five-year lease was £93,250. The rent was £5,750 a month. On the total package, therefore, Mama Ngina stands to receive £438,250,”

Former President Mzee Jomo Kenyatta.

According to the declassified documents, Kenya’s reaction to the Times expose started off in a relatively low-key manner at State House. While bidding farewell to the outgoing British High Commissioner, Sir Antony Duff, President Kenyatta expressed his deep distress at what he considered a personal attack on him by the British media. According to the papers marked ‘confidential’, Mzee went on to ask the departing High Commissioner to convey his complaints to London.

On September 9, just a few days after Kenyatta raised the matter with Sir Duff, Ngethe Njoroge, who by then was Kenya’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, called on the British Secretary of State and repeated the same sentiments. Ngethe argued that the British had timed the articles to appear just after President Kenyatta had assisted them in securing the release of Denis Hill, a British lecturer who was about to be hanged by President Idi Amin of Uganda. The allegations were denied by the Secretary of State who assured Ngethe that London had no foreknowledge of the articles and that it had no hand in their timing.

Ngethe reported to Kenyatta about the outcome of this meeting but a couple of days later made a formal protest to the British government by sending a note verbale written in strong language. The note, which was intentionally leaked to the media by Kenya before it reached its recipient, warned that the smear campaign against President Kenyatta and his family had to stop, otherwise Kenyans would take matters in their own hands.

“Following that interview, the High Commissioner reported back to the president and the former has been instructed to convey formally that the president of Kenya takes exception to the reports published in the Sunday Times because they seem to be deliberate attempt to vilify his person and to degrade his status as Head of State,” the note verbale begun. The note went on to defend the President’s family, stating that, “They are people of very humble beginnings who have had to struggle hard, together with the rest of the population in very difficult circumstances to emerge from the servitude of the past to lead a more dignified life.”

“It is known that the reports in question were prepared some time ago but it was thought prudent to postpone their publication to avoid upsetting President Kenyatta who was at the time assisting at the request of the British government, to save the life of Denis Hills, the British national who had been sentenced to death in Uganda on charges of treason. No sooner had Dennis Hills arrived safely on British soil than the Sunday Times unleashed its diatribe on President Kenyatta.”

The note further dismissed the press freedom argument, noting that, “In an advanced industrialised country, a Prime Minister can be hounded by the press as a matter of routine without any serious effects on the society. Not so in Kenya because the President there is a powerful, popular personality who symbolises liberation, parliamentary democracy, stability, progress, tolerance and unity all of which constitute the foundation of the modern Kenya state.”

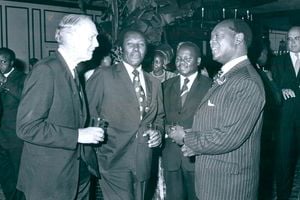

President Jomo Kenyatta with Vice-President and Home Affairs Minister Daniel Toroitich arap Moi.

The Kenyan High Commissioner wrote in conclusion: “There is a possibility that President Kenyatta’s political liberalism has been so misconstrued as to make one conclude that his government can be taken for granted. The President has instructed the High Commissioner to stress that if the campaign against him continues in the British media, his government will consider taking effective measures to preserve and protect Kenya’s interests.”

The British Secretary of State responded to Kenya’s complaints on that same day by emphasising that the British government had no control over the editorial policy of the British press.

“The independence of the press is a tradition of long standing in Britain; to attempt to change it would be to cut at the roots of the British Constitution,” he added. He, however, informed Kenya’s High Commissioner that it was open for foreign missions to ask the press for a right of reply to articles which could be interpreted as attacks on their countries.

Meanwhile, to calm the situation, the Foreign Office made a secret attempt to inquire from the Times about their sources, but the newspaper, in accordance with the well-established precedent, declined to reveal its sources. The Secretary of State obliged and wrote, “It is a feature of press freedom in this country that the government cannot force such disclosure.”

Irked by the Foreign Office’s hesitance to rein in The Sunday Times and take action against Barry, who had written the articles, Kenyatta sent his nephew Dr Njoroge Mungai to personally deliver his complaints to Harold Wilson, the British Prime Minister. This meeting did take place on October 7, 1975, and was also attended by the High Commissioner.

Mungai repeated Kenyatta’s complaints on the lines that were already familiar to British officials. The PM assured Mungai that the articles had no political repercussions in Britain and they would not discourage the government from continuing its aid programs in Kenya. He told Mungai that if he had control over the British press then they would certainly not publish some of the stories about him which appeared in the media.

Also Read: Charles Njonjo and Njoroge Mungai - Death, drama and sabotage in Jomo Kenyatta succession

He urged Kenya to consider taking legal action against the Times pointing out that the country had many good lawyers such as Charles Njonjo, who could always consider suing the newspaper for libel. However, he quickly added that he was giving the suggestion as a friend of Kenyatta and not as British Prime Minister. In conclusion, the High Commissioner said that attacking Kenyatta in the press could result in Kenyan citizens retaliating against British interests in Kenya.

While Kenya’s threats could pass for nothing more than a bluff, they did manage to cause some fear among some Foreign Office officials with the British High Commissioner to Kenya warning in a secret telegram to London that “The Kenyans might be pushed into taking some actions against British interests.”

He warned that it would be a bad situation if Kenyans directed their animosity against the BBC, whose monitoring service in Nairobi was important in collecting and analysing information using open-source intelligence.

On the same token, Kenya knew its position would be in great jeopardy if it took any steps which could affect British interests. It was bordered by aggressive Soviet backed neighbours who in pursuit of their expansionist policies were already laying territorial claims to some parts of the country.

Somalia, under Siad Barre, was claiming the North Eastern Province while Idi Amin of Uganda was claiming the area between Busia and Naivasha.

In fact, the previous year, on August 5, 1974, Bruce McKenzie, who had just left the government as Minister for Agriculture, had visited the British Prime Minister to express concerns about Communist rearmament of Kenya’s neighbours, in particular Uganda and Somalia.

- Mr Opiyo is a London-based Kenyan journalist and researcher