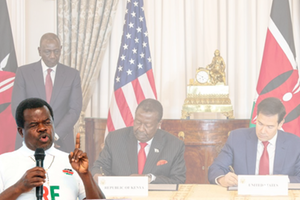

US Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Kenyan Foreign Cabinet Secretary Musalia Mudavadi sign the US-Kenya health pact as President William Ruto oversees.

What began as a health partnership with the United States has now become a flashpoint in Kenya’s foreign policy.

The signing of the US-Kenya health agreement has intensified scrutiny of President William Ruto’s foreign policy, with leading experts questioning whether the country fully grasps the implications of aligning too closely with an unpredictable Trump-era America.

Some diplomats and scholars have warned that the agreement could expose the country to geopolitical, legal, and strategic risks.

This, even as State House in Nairobi maintains that the pact represented an opportunity to boost Kenya’s health sector through technology, funding, and research.

For critics—especially seasoned diplomats and scholars—the deal signalled deeper risks embedded in the unpredictable currents of today’s global politics.

Among the leading voices questioning the move is former Kenyan ambassador to the US Elkana Odembo, who argues that the agreement exposes Kenya’s vulnerability in a world where great-power politics have rapidly changed.

According to him, the deal highlights a broader issue where Kenya struggles to establish a progressive, coherent, and comprehensive foreign policy framework, especially at a time when the United States is reshaping its global posture.

For decades, the US positioned itself as the champion of multilateralism—working through organisations like the United Nations, World Health Organization, World Bank, and various regional blocs.

President William Ruto (left) and his US counterpart Donald Trump.

These institutions formed the backbone of global cooperation, ensuring that powerful states did not act alone while smaller nations had platforms for representation.

However, under the Trump Administration, Washington has shifted dramatically, as the US president’s worldview is deeply skeptical of multilateral institutions, which he often criticises as burdensome and unfair to the United States.

His government has consistently favoured unilateral, transactional, deal-by-deal diplomacy over long-term international frameworks.

In Mr Odembo’s view, this poses a fundamental challenge for countries like Kenya.

While the US can afford unilateralism because of its wealth and military strength, he says, Kenya cannot.

“Nations of Kenya’s size depend heavily on the stability and predictability offered by global institutions—such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the UN, WHO, and emerging blocs like BRICS—all of which Trump has repeatedly dismissed or diminished.”

Mr Odembo argues that the timing is particularly striking.

“Even as Kenya prepares to host UNEA-7, a major global climate conference in Nairobi, the Trump administration has taken a confrontational stance against international climate action. Kenya has branded itself a global climate leader, investing in renewable energy and championing green financing. But the new pact with an administration skeptical of climate cooperation raises questions about compatibility and long-term diplomatic alignment,” he argues.

Mr Odembo’s critique also stems from the structural imbalance between Kenya and the US.

In global politics, he says, size matters—not only in population or GDP, but in strategic leverage.

The United States, he adds, negotiates from a position of overwhelming strength, while Kenya enters agreements with limited bargaining power.

“In the global context,” Mr Odembo notes, “Kenya is too small and insignificant to enter into any meaningful and mutually beneficial partnership with the US” unless it acts through multilateral platforms that can amplify its voice.

By stepping into a direct bilateral negotiation, he notes, Kenya risks being overshadowed by America’s national interests.

Adding to Odembo’s concerns, US-based Kenyan scholar Prof David Monda outlines several layers of risk surrounding the health agreement—ranging from data governance to great-power rivalry.

One of the most immediate questions concerns the handling of Kenyan health data.

President William Ruto and US President Donald Trump after witnessing the signing of a peace deal between DRC and Rwanda in Washington DC, USA, on December 5, 2025.

Prof Monda argues that modern health cooperation deals involve digital systems, biometric identification, epidemiological databases, and cross-border data transfers.

“Yet the legal framework that will govern these sensitive records remains unclear,” he says.

He asks whether Kenyan law will apply to the pact, and whether the data falls under US jurisdiction or whether the pact would be governed under the international standards.

“Without clarity, Kenya risks ceding control of personal health information to a foreign power—a troubling scenario in an era where data is considered the new gold.”

Prof Monda also describes Trump’s foreign policy as “contradictory and amorphously defined.”

Instead of a long-term strategic doctrine, he argues, Trump tends to pursue transactional gains—striking deals based on domestic political needs or personal impulses rather than consistent global objectives.

“This unpredictability makes it difficult for Kenya to plan. A project championed today could be reversed tomorrow. A commitment celebrated in Nairobi could be nullified by a shift in Washington’s political mood.”

Prof Monda also states that while former US President Jose Biden followed a more traditional, collaborative approach to global engagement, Trump represents the opposite—a return to “America First,” where alliances are fluid, and multilateralism is downplayed.

He argues that President Ruto is stuck between these two contradictory American foreign policy identities, hence Kenya must decide which worldview its long-term strategy aligns with.

For decades, he argues, USAID has been central to America’s “soft power”—helping nations through development assistance, humanitarian programs, and long-term institutional partnerships.

Under Trump, however, there has been a push to dismantle USAid’s multilateral structures in favour of bilateral agreements rooted in short-term political interests.

According to Prof Monda, this weakens the reliability of US cooperation and increases the possibility that Kenya may receive less favourable terms because of its relatively weaker bargaining power.

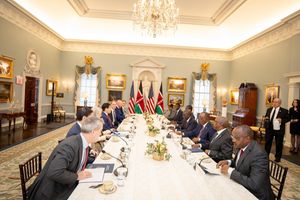

President William Ruto delivers his speech during the historic signing of a peace deal between President Donald Trump, President Félix Tshisekedi of the DRC and President Paul Kagame of Rwanda in Washington DC on December 05, 2025.

“Perhaps the most geopolitically sensitive issue is how the US-Kenya health deal will be perceived by China, one of Kenya’s most consequential economic partners. While the health agreement focuses on healthcare, it sends a powerful diplomatic signal that Kenya could be pivoting closer to the US at a time when the US and China are locked in a contest for global influence.”

China, Prof Monda argues, may interpret the move as Kenya joining the US sphere of influence, undermining Beijing’s efforts to build a more Sino-centric global order.

This, he adds, could complicate Kenya’s relations with China, which funds major infrastructure, energy, and technology projects across the country.

“For a nation that depends on balancing East and West, Kenya faces the risk of upsetting a partnership that remains critical to its development agenda.”

Both Mr Odembo and Prof Monda agree that Kenya must navigate the health deal carefully.

They argue that while the health agreement with the United States may bring benefits by improving health infrastructure, increasing collaboration, and attracting new funding, its potential downsides—if mismanaged—could leave Kenya exposed in a rapidly changing world.

State House, however, insists that President Ruto’s visit to the United States delivered landmark gains that firmly elevated Kenya’s place in Washington’s foreign policy under the Trump administration.

State House spokesperson Hussein Mohamed argues that the trip produced major breakthroughs in health cooperation, food security financing, debt restructuring, trade, and regional diplomacy—making it one of his most strategically significant foreign engagements.

“A central outcome was the signing of a $1.6 billion Health Cooperation Framework, the first such agreement under President Trump and the first globally under the new USAID model. The deal, a grant rather than a loan, builds on a 25-year, $70 billion health partnership and signals strong US confidence in Kenya’s governance reforms and UHC agenda,” Mr Mohamed says.

He adds that it also introduces, for the first time, a Government-to-Government funding model, enabling US health funds to flow directly into Kenyan systems such as Kemsa, NPHI, and digital health platforms—replacing donor-run parallel structures.

Follow our WhatsApp channel for breaking news updates and more stories like this.