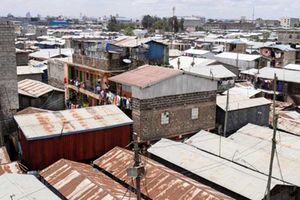

A section of Kibera slums in Nairobi County in this picture taken on July 13, 2025.

In our weekly series on living in Nairobi, Sammy Kimatu and Elvis Ondieki get schooled on which came first between ‘Kibra’ and ‘Kibera’, and are shocked to learn that there was a time when people could fish and play blissfully on the Nairobi Dam, on the fringes of the informal settlement, which is today a gooey mess.

When the name was first coined, it was “Kibra”. That’s how the Nubian tongue pronounced it. And for starters, “Kibra” in Nubian means “forest”. It was a dense forest when the first batch of Nubians, originally from South Sudan, made it their home. Actually, according to the Nubian elder Jamal Din, the land was given out by the British colonial administrators because it was deemed unsuitable for them.

“There was a huge forest there, and there were also a lot of streams. The British didn’t consider it a good place to stay for health reasons. They feared that wherever there were streams, there could be diseases like bilharzia, malaria, and others. So, when our forefathers retired, they were settled here,” says the 70-year-old, who is the chairman of the Kibra Land Committee.

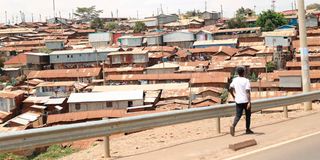

An elevated view of Kibera slums in Nairobi on November 24, 2019.

When Mr Jamal says “retired”, he is referring to the exiting from service by Nubian personnel who had been employed by the British Imperial East African Company in the late 1800s.

“Our story began in Southern Sudan when our ancestors were recruited into the British Imperial East African Company in 1890. They joined what was called the East African Protectorate and were admitted to the army – the King’s African Rifles – between 1890 and 1910. After being demobilised, the Nubians were settled at Kibra,” says Mr Jamal.

However, as was the case with Kaloleni that was given as a reward to former soldiers, the British did not take steps to officially allocate the land to the Nubians, and they lived there for years without any ownership documents. This exposed them to a number of problems.

As the area became more and more popular, an extra vowel was added, and to many it became Kibera.

When the Nubians first settled, Mr Jamal notes, it was a serene locality. The settlements were well spaced and every household had a farm beside it.

“It was a very nice village, very beautiful. I remember we used to have the Nairobi Dam, where there could be water sports, fishing, and such,” he says.

“There were streams criss-crossing the area, and we could get water from them. It was a very beautiful green village, and the elders planted a lot of fruits – mangoes, pawpaws, guavas, bananas. Because of the fruits, Kibera was called a shamba up to the 1960s. Every person had their home and a small farm next to it, plus livestock,” adds Mr Jamal, a former government employee.

Mr Jamal adds that when Kibra was surveyed in 1934, it was found to be 4,107.5 acres. The original Kibra started from Lang’ata Road and went all the way to the Department of Defence headquarters and all the way to Dagoretti.

For a long time, Kibra fell under the Lang’ata district. According to Kibra Deputy County Commissioner (DCC) Victor Kamonde, the Kibra sub-county was created in 2016.

A section of Kibera slums in Nairobi on April 6, 2025.

The sub-county hosts the grounds where the Nairobi Show is held, the Kibera Law Courts, and the Nairobi-Kisumu railway line cuts across it – at Laini Saba and Laini Nane. In 2013, the parliamentary constituency was named “Kibra” in a symbolic effort to restore the area’s historical identity.

“Kibra is known as Baba’s (former Prime Minister Raila Odinga’s) bedroom,” says Mr Kamonde. “This is where Baba used to sit while serving as the area MP for Lang’ata.”

When it achieved sub-county status, Mr Kamonde adds, the Lang’ata area was carved off.

“Kibra sub-county covers 12.5 square kilometres, according to the census of 2019, and has over 185,000 persons. We are what I may call one of the 18 sub-counties in the Nairobi region, and we are a sub-county that is mainly composed of informal settlements. We are in the villages, we are headquartered in the villages, but we are happy to serve the people of Kibra, although we have so many other challenges,” Mr Kamonde notes.

“We have nearly all the tribes of Kenya living in Kibra. It’s cosmopolitan, but it has the indigenous people, called the Nubians. They are the ones who were here first before others came in,” adds the DCC.

So, how did this transform from a serene, thick forest to a landmass of shanties that is one of the biggest slums in Africa? Mr Jamal says the reconfiguration began in the late 1960s.

“Kibra started changing from the 1960s. People started trickling in. They first came as workers; others as hawkers. Some women came from Dagoretti with green vegetables, eggs and other produce, to sell here. But then, Kibra suddenly changed, starting in 1969 after the death of Tom Mboya,” Mr Jamal notes.

After Mr Mboya’s assassination, he says, there was a lot of tension and “refugees” moved to Kibra.

“We received them well, they stayed here. That was from 1969 to 1970. There weren’t tenants because everyone was living on their property as the elders were working. Then they brought the issue of tenants. Slowly, they would come and ask, ‘Hello mum, dad; do you have a small space where I can stay?’” he recalls.

At the same time, politicians were eyeing sections of the city where they could easily get elected. Jamal theorises that due to political considerations, some “big tribes” were pushed into the area.

“The first big invasion and occupation came due to politics,” he says.

The massive land here, he adds, was tempting to many.

“There was a lot of open land. Laini Saba had only five families; Sarang’ombe had about 10 families,” he says.

As people saw the potential of building structures on the cheap and renting them out, structures cropped up all over. By the time Mr Odinga became the Lang’ata MP in 1992, Mr Jamal says, Kibra was “already full”. By this time, the Nubians had grown weary.

He remembers telling Mr Odinga: “This is our property that we were given by the British way back, but we are not benefitting from it, and we don’t have any documents to show – although records are there.”

A man washes clothes in populated water flowing in Kibera slums on March 16, 2025.

An admirer of Mr Odinga, Mr Jamal says the former ODM leader who died last month fought a lot to ensure the Nubians got documentation for the land.

“Kibera, being cosmopolitan, was not easy (to get the documentation),” he says.

“There were many people, and so how do you take a small community (Nubians) and give it land when that would mean driving away everyone else? So, it was a difficult process, but we thank Raila a lot. He raised the matter in 1993, but it was consumed by politics. Remember, he was in the opposition, and it would have looked very bad for the government of the day that an opposition leader would get titles for such a land.”

As the land ownership showed, it has always been a precarious situation for the Nubians, who for decades were not officially recognised as a Kenyan tribe.

In March this year, when he hosted Muslims at State House, President William Ruto said there were plans to formally integrate Nubians into Kenyan society. He hailed their contribution to Kenya’s history and promised to grant them citizenship status.

At a recent appearance in the Senate, Interior Cabinet Secretary Kipchumba Murkomen told the House that the National Registration Bureau has given the Nubian community a unique identification code.

“The Nubian community was officially assigned a distinct ethnic code, Code Number 50, in 2022, thereby recognising them as a Kenyan ethnic community within the national registration framework,” said Mr Murkomen after questions from Nairobi Senator Edwin Sifuna.

One of Mr Sifuna’s questions was: “Why does the Nubian community continue to face barriers in acquiring national identification documents, and what measures is the ministry taking to bring an end to this discrimination?”

In 2017, Nubians scored another win when President Uhuru Kenyatta issued a title deed bequeathing 228 acres of Kibra land to the Nubians.

The Nubian influence doesn’t end with the name “Kibra”. Even “Sarang’ombe”, one of the regions of the estate, comes from their language. “Sara” means “take care of” in Nubian and “ng’ombe” is the Swahili word for “cows”.

“The entire area from Toi Market to the Kibra Railway Station was open land. It was just grassland. Cows used to feed there, then go to Nairobi Dam to drink water,” says Mr Jamal.

Speaking of Nairobi Dam, Mr Jamal says the colonial government constructed the structure because “the place had many rivers and that was the catchment area”.

“Also, the Britons started the Nairobi Sailing Club, where they would come with their boats for water skiing, sailing, and all that in the dam,” he says.

And Laini Saba, Mr Jamal says, was a corruption of “Laini Shabaha”, as the area was used as a shooting range to sharpen the aiming (shabaha in Swahili) skills of soldiers. Besides Laini Saba, other Kibra villages include Laini Nane, Makina, Kambi Muru, Kambi Aluru, and Gatwekera.

A view of residential houses in Kibera slums, Nairobi on October 6, 2024.

With the surging populations, Kibra has had to confront many challenges.

“Looking at the social part of life, we have child abuse in the informal settlement. We also have GBV prevalent in many of the houses. We have the snatching of phones, muggings that were initially the order of the day, but we are really trying to fight it and have Kibra change the narrative from what it is perceived to be, to a better place that anyone would want to visit and walk around safely, in and out of Kibra,” says Mr Kamonde, the DCC.

Social organisations, youth groups, and community-based initiatives have flourished here. Local artists have gained international recognition for using music, film, and photography to challenge stereotypes about life in the slum. Projects like Kibera Town Centre, Shining Hope for Communities (Shofco), and the Kibera Pride Initiative have worked to provide clean water, education, healthcare, and women’s empowerment.

“Kibra people are very good people,” says the DCC. “They live like one community, bound by the same challenges, and are focused on finding and getting solutions to the challenges that they have.”